Filipinos, ghost workers in American fields

SAN RAFAEL, New Mexico — Many of us have heard of Filipinos. Someone we know has an aunt or cousin who was married to a Filipino or has tasted their delicious food. I wonder how many know that they worked side by side with Mexican migrant workers as well as local Navajos in the carrot fields of the Bluewater region west of Grants, New Mexico and east of Gallup, New Mexico. The carrot industry involved flesh and blood people, who worked hard in the fields and sheds harvesting carrots and other vegetables.

The success of farmer/landowners in planting mostly carrots in the area created a demand for efficient harvesting and packing of this particular vegetable. Having contacts with the many farming landowners, the Bluewater farmers asked that experienced crews stationed in the Phoenix, Arizona area come and harvest their carrot crop. Many Filipinos worked in crews that traveled from west to east and back harvesting various crops during the late ‘30s and ‘40s.

In the early ‘40s, our nation was at war, and the men from every state were sent to participate in it. Who was left to do the work that was left behind? Migrant workers and local women were swept into doing the work that needed to be done especially harvesting the produce to put food on the tables of Americans.

Why ghost workers?

Why do I say Filipinos were ghost workers? It’s because they blended in with the Mexican, Navajo, Chinese and Japanese workers. Their identity was almost invisible and they were in the shadows, so to speak. In two published accounts I have read, there’s no mention of Filipinos working in agriculture. I know firsthand that they worked in the harvest of crops in Bluewater because my father and his friends, all Filipinos worked there.

Filipinos were credited with introducing a way of packaging carrots that took less time and minimized damage on the produce. Filipinos and New Mexicans have a shared history since 1565, since the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade and the Spanish American War. The US bought the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam for 29 million dollars after the US defeated Spain in the Battle of Manila Bay.

My father was in one of the crews contracted to come and harvest the booming crop of carrots in the Bluewater fields. He had been in the country about 13 years. In 1927, he left the Philippines to pursue the American dream here in the United States. He had finished high school, so he knew enough English and Spanish to cope with new people.

He and about 100 young Filipinos came over on the ship the Empress of Asia. Most were from rural provinces from the island of Luzon. They boarded the ship in Manila and crossed the Pacific. They landed in Seattle, Washington, and from there they dispersed to different states to find work. This first group of pioneers just fended for themselves. In later years, immigrants had to have a sponsor or family to take you in and help out in finding homes and jobs.

My father’s life

A few years before my father died, I asked him if he would write down about his early years when he got to the U.S. He was already suffering from Parkinson’s disease and he had difficulty with his hands, but he tackled it by writing on a hard surface, which was cardboard.

He writes: He began his odyssey after he arrived in Seattle by moving to Salinas, California, where he worked on a farm for two years. After that job, he moved north to Alaska to work in a salmon factory. He came back to California worked there and then moved to Utah to work on the railroad. He kept moving because steady work was hard to get. From Utah, he moved to Omaha, Nebraska, following whatever work was available. He lived in Chicago, Illinois, for a time but with the discrimination against Asians because of the war, he suffered many hardships.

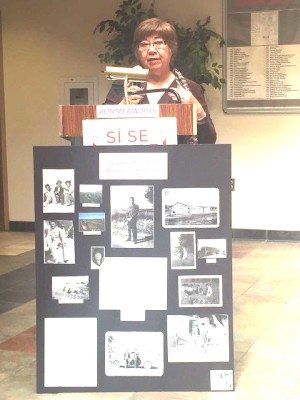

The author, Mary Ann DaSalla Montoya, speaking about her father’s life as a migrant farm worker in New Mexico. CONTRIBUTED PHOTOS

There’s one line in his account that always makes me cry. He writes: “You know, sometimes I got a hard time.” That’s the only line that gives a glimpse to the struggles he endured during that time. From Chicago he moved to Minneapolis and Mankato, Minnesota, to work at farms. From Mankato he traveled back west to Salinas and finally made Phoenix his home base. Many Filipinos lived there but followed the crop harvest wherever direction they were needed. In this area and across the country, they worked with the Mexican migrant workers and others.

Carrot Capital

The year that carrots were a booming crop Grants, New Mexico, was named the Carrot Capital of the world. The work crew had a limited choice of living quarters with some crude barracks close to the fields for some. The others, some with wives, were forced to rent rooms in the nearby village of San Rafael. There were not many rooms available in Grants.

At this time, many of the local young women were working at the packing sheds that packaged the carrots. Some had friends that were brave enough to go to the fields but were not capable of doing the back- breaking work. Remember Kevin Costner in the movie “McFarlane”? It’s not an easy job to do. Anyway, the Filipinos would help the “helpless dames in distress” and do their row of crops. That’s how many of them met for a brief time.

In the few weeks that they were in Grants and San Rafael, they attended local dances, which were a popular form of entertainment then. The Filipinos were dapper men who, off the fields, dressed in their best suits and were great dancers. I heard there were scuffles with the few men that were in town because of the interaction between their sisters and daughters and these “foreigners.”

In those few years where carrots continued to be successful, the Filipinos would stop and eventually became committed to a particular woman and ask her to marry him. Again discrimination was rampant, but Filipinos were intelligent and strong men, who had suffered other hardships. They won over the women they loved and if they couldn’t marry them in their hometown they eloped. Most of them moved to Phoenix as their home base and created their own community.

Proud

That’s how my parents met and later married. My mother was working at the hospital in Gallup when they decided to get married. My grandmother and uncles disapproved of it, but love won out. My father continued to follow the crop and most of the time my mother stayed in the Phoenix area until he returned from long-distance jobs.

My mother, who was Spanish, and my father, who was Filipino, joined their friends and relatives in creating what is today called the bridge generation. Children born between 1938 and 1945 were called the “bridge generation,” Manong/Manang generation.

In a different sense, the bridge generation suffered like their ghost farmer fathers. Again, prejudice reared its ugly head, and we suffered name-calling and bullying in our schools and communities. We are survivors much like our parents.

I’m proud of my father, Valentin DaSalla, who came from Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur, Island of Luzon in the Philippines. He and my mother, Flora, of San Rafael, New Mexico, had three children and their legacy at this time is eight grandchildren and nine great grandchildren and one great-great grandson.

Their love and steadfastness held them together until their deaths. He is the only Filipino buried in our village cemetery in San Rafael, New Mexico, USA. (Republished with permission from the Cibola Beacon.)