HE MAY well be called the “Pied Piper of Art Unbound,” the precursor of a movement to free one of India’s most elite art forms from the shackles of exclusivity.

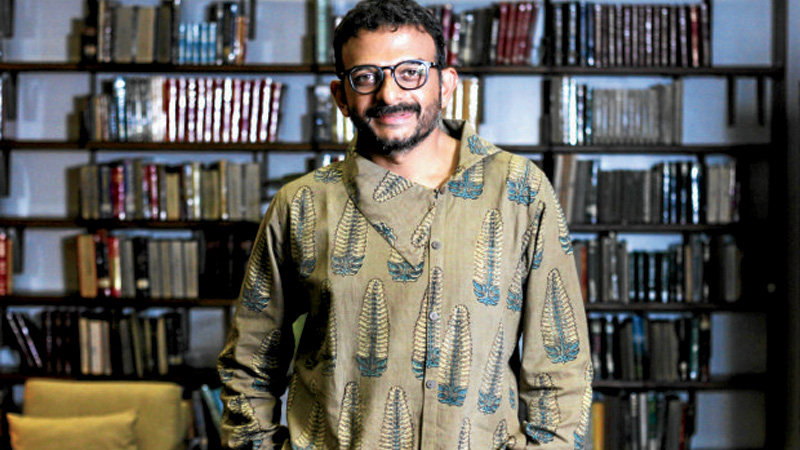

Then again, renowned Indian Karnatic musician and cultural activist Thobur Madabusi Krishna would likely disagree, being against labels, imposition and hegemony.

All he wants is to see free access to all forms of art—his genre of Indian classical music included—and bring into a single audience people of diverse tastes, backgrounds, race, social class, religions and political convictions.

“The point is not about liking or disliking… But it is, I think, the fundamental right of every human being to have unfettered, uninhibited, fearless access to every art and every culture. I think that’s a fundamental right, as much as education is a fundamental right,” Krishna said in an interview.

One of India’s most popular and most socially provocative Karnatic vocalists, Krishna is this year’s Ramon Magsaysay (RM) Awardee for Emergent Leadership, selected for his advocacy of dismantling the boundaries of India’s caste system by taking Karnatic music beyond class limits.

In announcing his citation, the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation said Krishna was recognized for “his forceful commitment as artist and advocate of art’s power to heal India’s deep social divisions, breaking barriers of caste and class to unleash what music has to offer not just for some, but for all.”

Getting people together

The award comes at a “very interesting time” for Krishna just as caste conflict continues to flare up periodically in his homeland, and as he has drawn both praise and criticism for his advocacy to liberalize all forms of art.

“The idea that art and culture have to be loosened from social and political systems that strangle them within communities, within people, within sexes, all that, and the fact that if you loosen them up, that is the way you can get people together, that is possibly how you can help people understand others,” he told the Inquirer.

Krishna grew up in privilege, born in 1976 to a Brahmin (highest among India’s castes) family that was into business. The Chennai native was exposed to Karnatic music early, training at age 6 in the aristocratic classical art form his businessman father, T.M. Rangachari, loved well.

Karnatic music is a centuries-old southern Indian musical genre that is performed by a vocalist, violinist, a tambura (drone) player and percussionists in a combination of both composed and improvised lyrics and melodies.

It has “never really been music for all,” said Krishna, with the music largely catering to India’s rich.

Krishna started performing Karnatic music at age 12, but had a “big dream” to pursue a career on the other side of the spectrum: economics. Taking on the art full time beckoned as early as 16, when old-timers in the Karnatic music circuit encouraged him to “take this seriously, you have some talent.”

He still finished his degree, but readily shifted to Karnatic singing full time.

In his first few years, he enjoyed the celebrity, singing in packed concert halls filled with spectators from his own caste.

Purpose of it all

“For many years, I sang like a musician. I wanted to be rich and famous, as they say. Of course, I loved the adulation. I loved the applause,” he said.

But in early 2000, Krishna started to question the purpose of it all. Exposed to the teachings of Karl Marx, Jean-Paul Sartre and Indian thinker Jiddu Krishnamurti both at home and in school, the emerging star started to seek deeper meaning for his art.

When he was “almost at the top” of his career, he took a step back and wanted to understand his music better by researching on the history of Karnatic music.

Krishna has authored a book on the subject titled “A Southern Music: Exploring the Karnatic Tradition,” which he described as “a philosophical and sociopolitical inquiry of the art form.”