Review: ‘Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes’

The first time I encountered the Marcoses was in 1964 at a Democratic fundraising barbeque on the lawns of one of those sprawling Long Island homes. The party was being hosted by the actor, Paul Newman, and Lynda Bird Johnson, and was in aid of her father’s reelection. Late in the evening I found myself rubbing shoulders with Senator Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, the Philippines Presidential candidate, and his wife, the beautiful Imelda Romualdez.

As a woman I should probably have had some feminine intuition here for, in a few short years, I was to become an outspoken adversary of theirs. I would write exhaustively on the ill-gotten gains of their conjugal dictatorship. I would speak out publicly against their excesses. And I would mourn the loss of several of my young friends — poets, artists and political activists — whose vital young lives were cut short by members of the Philippine Army or Philippine constabulary acting on the orders of the Marcoses. But there was no way of knowing then what a central part of my early life this couple and their country would become. So I shook their hands, smiled politely, made some innocuous remark about the evening and walked away.

Now, 30 years later, with the subject almost exhausted by the sheer number of books, articles and theses having been written about the Marcos period, I imagined it would be virtually impossible for any writer to uncover anything new.

Very bright light

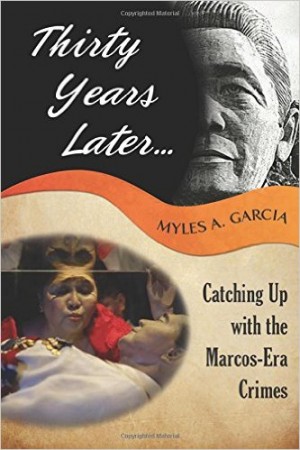

But here, in “Thirty Years Later – Catching Up with the Marcos Era Crimes,” Myles Garcia has not only proved me wrong but has managed to shed a very bright light on the ongoing financial and criminal investigations still facing Imelda Marcos, her immediate family and friends.

Did I already know, for instance, that if either Imelda or her son, Bongbong, were to set foot in the U.S. they would be apprehended immediately for failing to abide by a $2 billion judgment by a U.S. court in favor of victims of human rights violations by the Marcoses?

Was I aware that both Imelda and Bongbong are also incurring fines of $100,000 a day for non-compliance of the ruling and a further $353.6 million fine for contempt of court? And did I know that on appeal to a higher court against these by the Marcoses that both judgments had been upheld?

Did I know that two of Imelda’s best friends, Glecy Tantoco and Vilma Bautista, had both been sentenced to prison? The latter to six years by the New York District Court for having sold Imelda’s illegally-acquired painting, Claude Monet’s “Japanese Bridge over the Water-Lily Pond at Giverny”, for $43 million and for tax evasion. And Tantoco was arrested in 1986 at Rome Airport on the orders of the U.S. Attorney’s Office in New York and was jailed for 70 days while fighting extradition to the U.S. She was freed after claiming “a heart condition” and she and her husband then fled Italy and did not surface again until1994 when she flew to the U.S. for medical treatment but died in hospital that same year.

Passion

I knew none of this because I have had neither the patience, nor the time, nor the stamina over the intervening decades to persistently make applications for court records, or to approach the PCGG to obtain copies of all outstanding lawsuits against the Marcoses or to trawl through mountains of legal documents examining the details of each case.

I admire Garcia for having the commitment to familiarize himself with all the details. The passion in his book shines through its pages. It is immediately obvious the author has spent long hours reading countless newspaper reports and a whole library of books and articles about an infamous era of Philippine history – the 14-year authoritarian rule of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.

“Thirty Years Later” provides any student of Philippine politics with well-documented proof of the “ill-gotten” gains and the systematic and wholesale looting of government funds and foreign aid programs that took place during Marcos’s presidency and from which the country has still not recovered.

Another current Marcos myth punctured by Garcia is that when Marcos switched political allegiances and became the Nacionalista Party Presidential nominee in 1965, and contrary to recent propaganda put out by the Marcos family, he was not rich. He had made money before he became President, lots of money, yes. But in order to clinch the nomination he had spent it all. He was even forced to select one of the country’s richest oligarchs, Fernando Lopez (owner of Meralco), as his running mate with the understanding that Lopez’s money would be spent on their joint campaign. Since a major platform of Marcos’ election was to rid the country of its oligarchs his selection of Lopez might have been seen as a sign that Marcos was, at best a pragmatist and, at worst, a hypocrite.

Timely

This book is timely. Filipino elections will take place in May 2016 and a new generation of the Marcos family is involved. Bongbong Marcos is running for the Vice Presidential post. This now begs the intriguing question that, should he win the nomination, would he be able to travel freely to the U.S. without risking arrest? I don’t know the answer to that and Garcia doesn’t speculate. But I can only imagine it would be acutely embarrassing to the Philippines if their Vice President was placed in handcuffs once he stepped foot on the tarmac immediately after landing at a U.S. airport.

The mere fact that Bongbong has a good chance of being elected and, thus, using it as a springboard to a future Presidency is a dire comment on the integrity of the Philippine educational system that it has failed abysmally in its duty to teach the truth about the Marcos era to ensure it will never be repeated.

For all students of history and politics, this book is a must-read. If you can get your head around all the facts, figures, numbers and dates you will be amply rewarded by a fascinating insight into what can go wrong when one man takes the reins of power and exacts his will on both the people and the country and his revenge on all those who disagree with him. “Thirty Years Later” should be compulsory reading material in all schools in the Philippines. It offers a lesson for future generations.

Those who lived through the Marcos era have a duty to inform the younger generation — the “millenials” — just how much money was stolen from the country, how so many people lost their lives and how the Marcos family, even after three decades, is still denying its victims financial compensation that has been awarded to them by courts both in the US and the Philippines.

“Thirty Years Later” does just that.

Caroline Kennedy is a traveler and a writer. In 1987 she wrote the number one best-selling book, “An Affair of State”, later made into a musical by Andrew Lloyd-Weber, entitled “Stephen Ward.” She has worked in Bosnia during the war bringing medical and surgical aid to the hospitals, orphanages and homes for disabled children. She has just produced an anti-war CD in aid of the child victims of the Iraq War and is now working on her memoirs. She was formerly married to the Philippines National Artist, Bencab, and has three children, Elisar, Mayumi and Jasmine.

Like us on Facebook