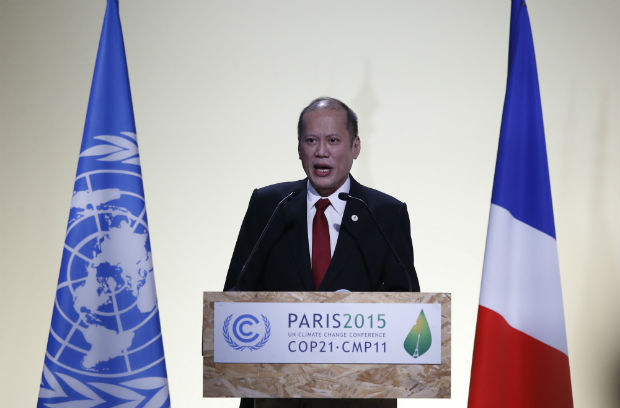

President Benigno Aquino III delivers his statement at the COP21, United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Le Bourget, outside Paris, Monday, Nov. 30, 2015. AP

PARIS—President Benigno Aquino discharged the duties of a coalition chair at Monday’s start of the historic climate change negotiations in this city. He used the three minutes allotted to every head of state or government addressing the 21st Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to speak, not only of the Philippine situation, but also of the fate of other countries vulnerable to the severe consequences of climate change.

Thrice in his short speech, Mr. Aquino referenced “countries like the Philippines [that] bear a disproportionate amount of the burden when it comes to climate change.” The language of disproportion has been used by the Philippines before, at the Copenhagen COP, but as chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, President Aquino used it to draw attention to other countries at risk.

“How do we ask everyone to contribute, and how do we ask those with more to help out those with less? Consider the case of the most vulnerable countries, like the developing island state of Grenada, which sustained damages that amounted to more than 200 percent of its GDP in 2004.”

Two more times the President cast a wider net, warning about “the danger faced by island-nations such as Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Maldives, whose existence is threatened by rising water levels,” and noting that the climate-vulnerable countries he had led for a year was “a group that will soon grow to represent at least 1 billion people.”

The full text of President Aquino’s “national statement” at the COP21 Leaders’ Event follows:

Excellencies, last February, our good friend President Hollande and I launched the Manila Call to Action on Climate Change. At the heart of this call is the stark reality that countries like the Philippines bear a disproportionate amount of the burden when it comes to climate change. The appeal we made in Manila asks all peoples to act and come to an agreement that allows all voices to be heard, and takes into consideration our particular situations as nations.

As President of a nation increasingly affected by the new normal, I believe the real challenge begins with an accounting of capacities: How do we ask everyone to contribute, and how do we ask those with more to help out those with less? Consider the case of the most vulnerable countries, like the developing island state of Grenada, which sustained damages that amounted to more than 200 percent of its GDP in 2004. If they lose so much, then their capacity to contribute in our efforts is also dramatically diminished. I am told that the economic costs of climate change amount to 44.9 billion dollars annually for the Vulnerable 20 countries. Inaction will cost us even more, as this number is set to grow almost 10-fold by 2030, amounting to 400 billion dollars.

We are also told that, since 2010, on an annual basis, climate injustice has claimed more than 50,000 lives from V20 countries—and this number will increase exponentially in the near future. Consider further the danger faced by island-nations such as Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Maldives, whose existence is threatened by rising water levels. Their extinction will be a certainty, unless we pursue realizable goals that acknowledge that, for some nations, the fight against climate change is a matter of survival.

In our own experience in the Philippines, we have been working to break the vicious cycle of destruction and reconstruction, where affected locales, especially our coastal communities, slide back into an impoverished state with one calamity. The primary challenge has been to move our countrymen to less vulnerable areas, on the assumption that such exist—or to make interventions that mitigate the impacts of climate change. We are indeed hard pressed to build back better especially in the aftermath of Haiyan, and I must submit: We cannot do this in isolation.

Let me point out, however, that despite our fiscal limitations, and despite the fact that we have one of the smallest carbon footprints in the world, the Philippines continues to pursue vital reforms to address climate change; and I say that we are willing to share our experiences, knowledge, and best practices. We have expanded a massive re-greening program. We started the program in 2011; the goal is to plant 1.5 billion trees in 1.5 million hectares by 2016. Upon completion, this would translate to an absorption capacity of 30 million tons of carbon annually. To this end, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, in its Global Forest Resources Assessment for 2015, has named our country as one of the top five nations with the greatest annual forest area gain.

We have also intensified our anti-illegal logging campaign, reducing by 88 percent the number of municipalities and cities in my country considered to be illegal logging hotspots. We are likewise increasing the share of renewables in our energy mix, which now accounts 33 percent. We have put in place the policies and legislation, and allocated the funds to address climate change as far as our resources will allow. This year alone, about 5% of our total budget was allocated for climate change. Furthermore: Just this October, the Philippines submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions or INDC, committing our country to reducing our greenhouse gas emissions conditionally by 70% by 2030. We are ready to do our part, if other nations demonstrate support in terms of finance, technology development, and capacity building.

Today, the Philippines, with the rest of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, a group that will soon grow to represent at least 1 billion people, makes our case. In the name of all our citizens, we ask you to give our proposal for more climate financing for developing countries the consideration it deserves. We likewise seek your support as the CVF finalizes the Manila-Paris Declaration, which presents our aspirations for a world that is resilient and just, one where no one is left behind.

Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, what our nations failed to do in Copenhagen in 2009, we must achieve here in Paris in 2015. It is time for a fair consensus to finally be reached. Our collective security depends on our ability to act. We must therefore move beyond recrimination, learn from the past, and work hand in hand to safeguard the welfare of our citizens and of the many generations to come. In this effort, no one is exempt; all must contribute.

Thank you and good day.