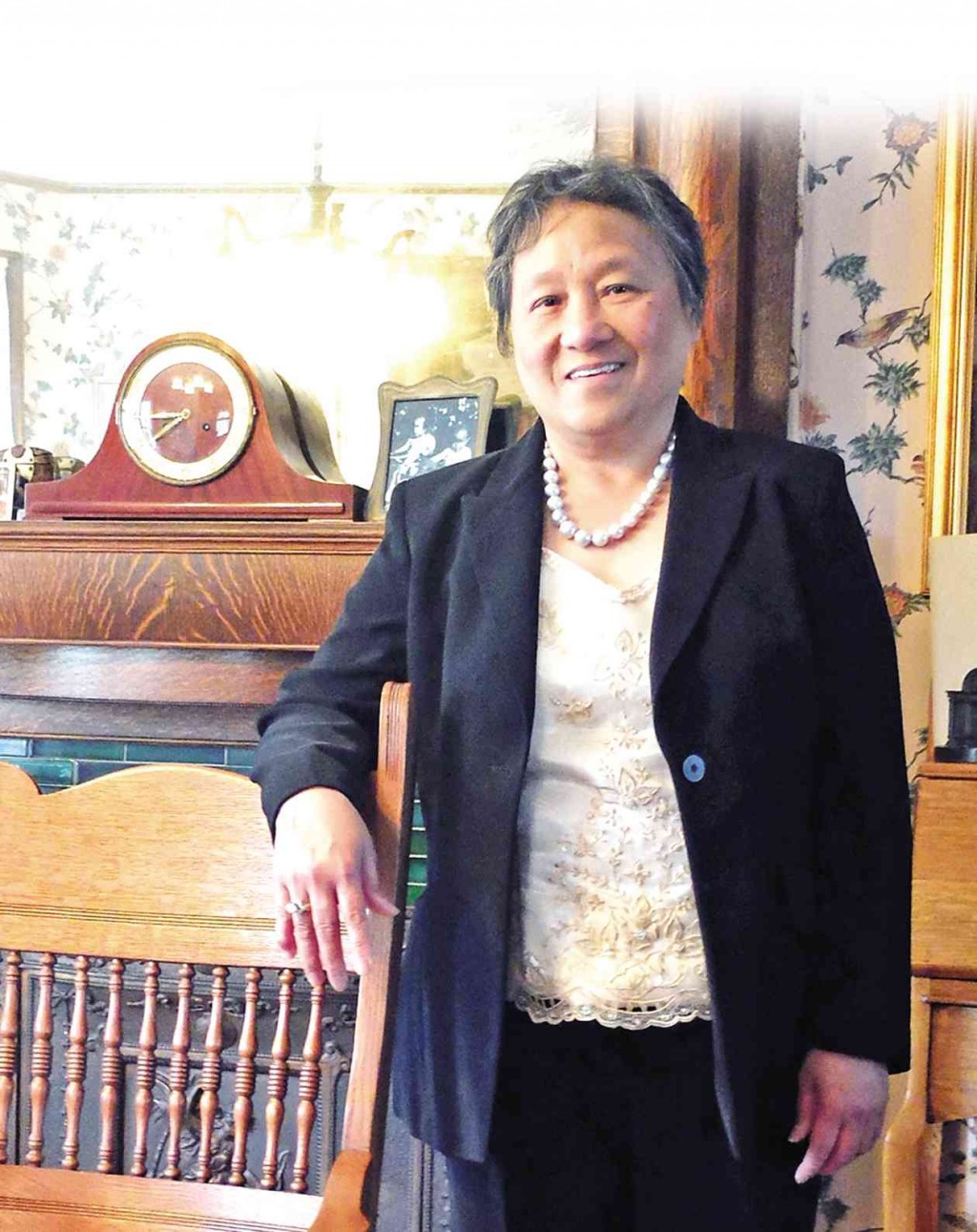

Woman of action.For Therese Rodriguez, writing their commemorative book “was a healing process of sorts. Fifty years gave me perspective and answers on why I had such a nebulous and negative feel of high school days.”

Though St. Scholastica’s College (SSC) Manila’s High School Batch ’66 officially celebrates its golden jubilee on February 2016, seven of its US-based alumnae experienced a reunion of sorts with their fellow classmates when they took on the formidable task of putting together a book about what became of the 92 kulasas since graduating from their alma mater.

“Our Stories to Tell: 50 Years in Retrospect” features first-person essays on what transpired in the lives of each classmate, post-SSC.

First pitched during the batch’s sapphire jubilee in 2011, the commemorative book took off with the distribution of a detailed questionnaire to batchmates during a birthday lunch for August- and September-born classmates in Manila in 2013, followed by the formation of the SSC High School 1966 Golden Project Team in New York City on September of the same year.

Sleuthing for whereabouts

Therese Rodriguez served as the book’s editor in chief, Chita Sevilla its senior editor, Tess Calupitan-Medina its managing editor and Chit Quimbo-Rader its art design coordinator. Aya Villegas, Carol Salas-McCluskey and Tim Rodriguez-Manalo were editorial assistants.

“The process was a great adventure in international ‘detective’ work by sleuths Aya, Tim and Carol, utilizing both the Internet and social media to trace classmates’ whereabouts,” says the New York-based Rodriguez, who shared the responsibility of writing and interviewing with Medina and Sevilla.

Extreme patience

The trio also relied on the answers to the questionnaires, which the team received “in various states of unfinish,” wrote Medina in the “Behind the Scenes” section of the book, “from 2,000-word narratives to scribbled random thoughts.” Rekindling relationships with classmates they hadn’t seen or heard from in decades was thus inevitable, a challenge that required extreme patience and perseverance on the part of the writers—and unequivocal trust on the part of respondents.

P.S. we tried to reach you

In the end, the painstaking effort yielded 82 essays and “a whole new relationship among classmates who have not been in touch for 50 years,” says Rodriguez. (Classmates who had since passed on were honored in an “In Memoriam” poem, while those who could not be reached or chose not to participate appeared in a section called “P.S. We Tried To Reach You.”)

At 196 pages, “Our Stories to Tell” is more than a way to catch up with old classmates. “It’s a legacy to our children and the generations to follow,” says Medina, to which McCluskey adds, “Hopefully, anyone who will read our golden book will conclude that, indeed, the Benedictine values are well-rooted and alive in our class.”

Healing process

For Rodriguez, the book “was a healing process of sorts. Fifty years gave me perspective and answers on why I had such a nebulous and negative feel of high school days,” she says.

Describing her high school self as “far from an academic high achiever” (though ironically, classmates remember her as the one who was “always studying!”), Rodriguez proved a woman of action, throwing herself wholeheartedly into causes worth fighting for.

Graduating with a business administration degree from St. Theresa’s College in the early ’70s, the young idealist was part of the protest movement. She published material exposing graft and corruption, and opened her Parañaque home to moderates and communists, “to the great dismay of my mother, a devout Catholic from a landed family,” she writes in her profile.

A year later, she traveled to the US, and was forced to stay there when then President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on Sept. 21, 1972.

Facing military arrest

Facing arrest from the military should she set foot in the Philippines, Rodriguez, a member of the US-based anti-Marcos Dictatorship Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino, remained in the US for 14 years, missing key family events like the burial of her beloved Ninang Pitang, an unmarried aunt who raised her, along with her mother Corazon and maternal grandmother Eusebia.

Even in the US, Rodriguez found a way to make a difference in people’s lives, organizing Filipino-Americans against racial and national discrimination faced by the community.

She worked briefly at the Center for Immigration Rights, a job that led her to an administrative post in the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services, a social service agency of the Lutheran Church that resettles European and Asian refugees in the US after World War II and the Vietnam War.

In October 1996, she joined the Asian and Pacific Island Coalition on HIV/AIDS (Apicha), then evolving from a grassroots volunteer advocacy organization to a community-based organization (with a paid professional staff) that offers community outreach, prevention programs, and direct services to Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV and AIDS.

Hired as its executive deputy director, she took over the organization when her boss, the executive director, left his post two weeks into her job. In March 1997, Apicha made it official; Rodriguez was promoted to executive director.

Despite threats of closure during America’s recession, Apicha has grown by leaps and bounds under Rodriguez’s helm. From providing medical services to people living with HIV/AIDS to offering primary care to those who are at high risk for HIV infection, the organization now extends its services to members of the LGBT community and other communities of color, like African-Americans and Latinos.

In 2011, a pledge from a private foundation allowed Apicha to open a Trans Health and Wellness Clinic, further extending help to the growing transgender community.

Indeed, the organization now known as Apicha Community Health Center (ACHC) has of late been the recipient of generous grants, including one for $6 million from the New York State Department of Health in 2013.

Challenges

Last August, ACHC received a New Access Point Award from the federal Health Resources Services Administration, a grant that supports the center with $650,000 annually for the next two years. More importantly, this milestone allows the organization to work toward becoming a federally qualified health center, a status that bodes for more substantial benefits.

Besides grappling with the challenges of the communities she serves, Rodriguez has her hands full as ACHC’s CEO. An immediate goal is to open another community center colocated with an LGBT center in Queens, New York.

Quality care, services

“A major challenge as we grow is to maintain our commitment to quality and culturally competent care and services, especially for our legacy populations—people living with HIV, LGBTs, Asian and Pacific Islanders, and other communities of color,” she says.

“Transformation management requires investment in new infrastructure, upgrading, training and retooling the skills of all staff. [For me, it means learning] the business of a community health center in a rapidly changing health-care environment.”

For all these major plans and developments, Rodriguez unexpectedly entertains thoughts of slowing down. “I need to plan for retirement,” she reflects. “Perhaps now I can do what I had originally wanted to do: travel between the Philippines and the US, make longer visits to the Philippines for more consequential causes and relationships.”

A health center in the Philippines a la Apicha is not far-fetched, she says, “but it must be done by someone who truly understands the Philippines and can navigate the health and political terrain in the country.”

True to her nature, this woman of action will be there to help. “I’ve been away for so long,” she admits. “However, I would be more than willing to give whatever resources I can provide.”