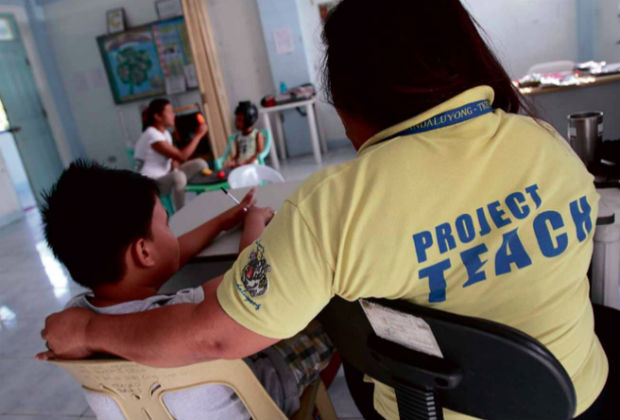

A volunteer teacher attends to an indigent special child in Mandaluyong City’s award- winning Project Teach. RICHARD A. REYES / INQUIRER

Why is my kid different?

Leonora Zuniga began to ponder over this question when, early on, she noticed her daughter exhibiting traits strikingly different—and unusual—from those of her twin brother.

“It’s very difficult to teach her. It seems like she’s not listening and she’s not focusing,” Zuniga said of her 10-year-old daughter, Joanna Esther, who was diagnosed with autism in 2009.

She first came to know of her daughter’s condition after she was told by her twins’ daycare teacher that Esther had special needs. The next thing she knew, she was heaving a sigh of relief.

“I had a sense of relief since [at the time] I didn’t know what I was supposed to do with her,” Zuniga told the Inquirer.

She said she also found comfort in the fact that there was a local government initiative that would attend to Esther’s needs free of charge—Mandaluyong’s Project Teach (Therapy, Education, Assimilation of Children with Handicap) in Barangay Addition Hills.

The 8-year-old community-based rehabilitation program, a partnership with nongovernment organization Rehabilitation and Empowerment of Adults and Children with Handicap, caters to youths with disabilities from the city’s indigent families. It provides free services such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology as well as special education classes to children with special needs.

UN distinction

Volunteer teacher Leonora Zuniga relates how her own daughter’s handicap led her to become an expert in child behavior. RICHARD A. REYES / INQUIRER

Project Teach recently placed second in improving the delivery of public services category for Asia-Pacific of the 2015 United Nations Public Service Award, alongside Indonesia’s Fostering Partnership between Traditional Birth Attendants and Midwives to Reduce Maternal and Infancy’s Mortality. It will be feted in a ceremony during the UN Public Service Forum, which will be held at Medellin, Colombia, from June 23 to 26.

In 2012, Project Teach was also one of 10 local government programs recognized in the Galing Pook Awards. The award was handed to innovative programs that exhibited positive results and empowered citizens.

Zuniga credits Project Teach for the development her daughter has shown over the last five years.

“She now sings and is responsive when asked,” Zuniga said of her daughter, who is also a member of the city’s Children with Disabilities Drum and Lyre Corps, which has played at the Correctional Institute for Women, among others.

Zuniga can call herself an expert on children’s behavior, having looked after students when she worked as a teacher assistant and eventually as a supervisor at Called Out Christian Academy in Mandaluyong City for almost two decades.

Groping in the dark

When Zuniga gave birth to her twins, the school had already closed down. Having more time on her hands, it was not difficult to convince herself to be a “hands-on” mom.

“I’ve taught and handled a number of kids and yet I can’t take care of my own? I can’t fathom that idea,” she said.

She said she also contemplated moving to her hometown in Cagayan Valley months before being accepted into the program.

“I was thinking, if we move, we have relatives who can watch over her (Esther) and I’d be able to get back to work and have the income for therapy,” Zuniga said.

Zuniga added that it also came to a point that she “almost lost hope” because none of her friends knew what she was going through.

“I thought autism was just for the wealthy…. It came to the point that I almost lost hope. I felt so sad because none of my friends could help me [cope], I was groping in the dark,” she said.

Free therapy

The free therapy at the center over the years meant a lot to the family, especially since her salesman husband was single-handedly earning a living for the family.

Special children gather in front of their school building in Mandaluyong. RICHARD A. REYES / INQUIRER

On average, the family would have spent P147,500 annually for Esther’s therapy and education.

Esther, who is still undergoing occupational therapy and speech pathology at the center, is now studying in a non-special education school. Her mother proudly told the Inquirer that Esther finished fourth in her Grade 1 class at Eulogio Rodriguez Integrated School.

This was made possible through Project Teach’s bridging program, which equipped her with the necessary skills and competencies she needed for a formal education.

Project Teach’s Karen Jeorgha Ballad-Bobier said developments achieved by the likes of Esther made their job more “worthwhile.”

“I feel very proud and very happy. It feels like I was able to pay back to the society, which paid for my education,” said Bobier, a physical therapy graduate of the University of the Philippines. “[The experience] that you are able to help people make their life less burdensome is priceless.”

She said the UN recognition was a testament that “we are doing something right.”

“[With the recognition], we hope the project will be replicated in other cities and municipalities,” Bobier said.

Replicating the program

To date, Bobier said, around a hundred city and municipal governments have visited their facility to inquire on how it is managed and sustained.

On the day the Inquirer met Bobier, officials from Naga City and San Miguel, Iloilo province, had just visited the facility.

While many have “expressed interest” to replicate the program, only the municipality of Carmona, Cavite province, and Dipolog City have come up with community-based rehabilitation programs similar to Project Teach.

Bobier said she hopes the other local governments would follow suit as more and more children are being born with special needs.

In Mandaluyong alone, 2012 data showed that 600 children were recorded to have special needs. Of this number, 18 percent are suffering from mental retardation, 16 percent from cerebral palsy and 15 percent from autism.

Bobier said the facility had already catered to around 700 children since it started.

In return for the free services offered by Project Teach, parents participate in community services for the facility, namely, information dissemination, program support, family support and housekeeping.

Zuniga currently works as a parent volunteer at the facility, guiding parents who are new to the program, so “they wouldn’t feel left in the dark.”

Basic human right

She said her eldest daughter, Ethel, is studying occupational therapy at UP Manila so she could return the favor extended to her sister.

Bobier said facilities such as Project Teach were important in every area, since special children, especially those coming from the urban poor, were still members of our society.

“We don’t want to deprive them of their right to proper education. It’s a basic human right. It just so happened that they needed special attention for them to able to thrive in the community,” she said.