Remembering the First Quarter Storm

The Japanese occupation of the Philippines represented the most traumatic collective experience of my father’s generation. For my generation, the closest equivalent was the military occupation of the Philippines by the martial law dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, which also featured executions, tortures, rapes and countless violations of civil rights.

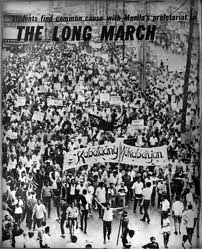

The “cathartic” prelude to Marcos’ imposition of martial law was the First Quarter Storm, which began 45 years ago this week.

January 26, 1970 was the opening day of the Philippine Congress and a newly reelected Marcos was set to deliver his version of the State of the Nation. But outside the Congress, various student groups had also planned to deliver our version of the true state of the nation in a mass rally jointly sponsored by the “moderates” led by Edgar “Edjop” Jopson, president of the National Union of Students of the Philippines (NUSP) and the “radicals” led by chairman Fernando “Jerry” Barican of the University of the Philippines (UP) Student Council.

I was part of the rally organizing committee as president of the National Union of High School Students (NUHS) which was aligned with the NUSP and so I participated in the meetings which drew up the program and the order of speakers.

Quarrel over the mike

As agreed, Edjop was the featured speaker and his speech was timed to coincide with Marcos delivering his state of the nation address. When Edjop completed his recitation of the abject conditions of the country, he called on Gary Olivar, a leader of the “radicals”, to speak according to the program we had agreed on. Even though I was aligned with the moderates, Gary was my neighbor and one of my closest childhood friends and so I rooted for him.

Gary was just about to speak when Edjop changed his mind and handed the mike to radio commentator Roger “Bomba” Arienda. But a s Roger was delivering his speech, the crowd kept chanting “Gary! Gary! Gary!” Instead of turning the mike over to Gary after Bomba concluded his tirade, Edjop unilaterally decided to end the rally by singing the national anthem.

Edjop feared that Gary would only inflame the rally and that it might turn violent so he acted to avert it. But just as the long rally was about to end at 6 p.m., a young labor leader grabbed the mike from Edjop and started delivering a fiery speech.

In his book, Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage, Jose “Pete” Lacaba described what happened next: “Passions were high, exacerbated by the quarrel over the mike and the President had the bad luck of coming out of Congress at this particular instant.”

Marcos and his First Lady, Imelda Marcos, were about to board the presidential limousine when someone hurled a crocodile papier mache in their direction. It missed its target but it ignited a fury of retaliation by a phalanx of riot police who swung their rattan truncheons at the heads of students – moderates and radicals alike – unifying us in our common pain, as a stunned nation watched transfixed on live TV.

Indignation rallies

In the days that followed, indignation rallies denouncing police brutality were held in campuses throughout Metro Manila culminating in the January 30 March to Malacanang from Plaza Miranda through the Mendiola Bridge. By nightfall, thousands of students surrounded the heavily fortified palace when suddenly the lights were shut off.

The Metrocom riot police retreated into the night, replaced with battle-hardened army soldiers armed with high-powered Armalite rifles out to quell a rebellion. Before that long, dark bloody night was over, four students lay dead, scores paralyzed, and hundreds maimed from gunshot wounds.

My Philippine Science High School schoolmate, Mario Taguiwalo, recalled that fateful night: “The death of friends, the terror of gunfire, the taste of truncheon taught a lot of ‘isms’ in one night. By the morning of January 31, 1970, a thousand chapters of student organizations had begun taking root in schools and communities nationwide.”

After the January 30 siege of Malacanang, the student groups formed a coalition, the Movement for a Democratic Philippines (MDP), to coordinate the demonstrations and rallies. It was headed by Julius Fortuna with Nelson Navarro as our spokesman. I was appointed to the 10-member Secretariat in charge of finance together with Raquel “Rock” Edralin of the Kabataang Makabayan (KM). Rock, a distant relative of Marcos, was the most courageous and fearless activist I had ever met. She would later marry Rigoberto “Bobbi” Tiglao, a fellow activist.

For t he next three months, there would be protest demonstrations, rallies, and “people’s marches” that all came to be called The First Quarter Storm, which Nelson Navarro described as “that cathartic student revolt in the first months of 1970 that shook the nation with its intense and all-encompassing life-changing experience.”

Life-changing experience

One “life-changing experience” for me occurred in a rally in front of Malacanang when a Metrocom soldier struck Rock to the ground instigating a violent confrontation between the Palace guards and the student activists. I saw the soldiers fall in formation, raise their rifles to shoot us, and then fired.

I turned to run away when I felt a sharp pain at the center of my back which caused me to fall to the ground. I was too young to die, I told myself as I lay on the ground with the smell of gunpowder and Molotov cocktails all around me. When I reached to touch the center of my back, I felt no blood, just a painful lump. To my relief, the soldiers had used rubber bullets, probably the last time they would do so.

In January of 1971, my parents “exiled” me to San Francisco, fearful that I would share the same “salvaged” fate of so many student activists, like my friend, Charlie Del Rosario, who attended an MDP meeting one night and then disappeared, never to be seen or heard from again.

When Marcos declared martial law in September of 1972, he imprisoned thousands of activists, including many of my friends like Gary, Edjop, Mario, Jerry, Rock and Bobbi. My father told me that two jeeploads of soldiers came to our home to arrest me that night even though I had already been out of the country for 18 months.

Living through the martial law years in the United States, I published the Kalayaan-International, taught Philippine history and political science at San Francisco State University and at Laney College, and organized the National Committee for the Restoration of Civil Liberties in the Philippines. I went to law school, passed the bar, set up my private law practice, was appointed president of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and was elected to the San Francisco Community College Board, the first Filipino elected to public office in San Francisco.

Back for a reunion

Twenty-five years ago, on January 30, 1990, I returned to Manila to attend a reunion I had organized, a gathering of friends at Freedom Park in Malacanang Palace, to mark the 20th anniversary of the First Quarter Storm.

No longer present was my friend, Edjop, who became a revered people’s hero after he was beaten, tortured, jailed for his underground anti-dictatorship efforts, and later executed by the military on September 20, 1982 when he was barely 34 years old.

But Jerry Barican was there. Once the radical president of the UP Student Council, he had become a staunchly conservative lawyer who justified his sea change by paraphrasing Churchill, “If you’re not a radical by 18, you have no heart. If you’re still a radical by 30, you have no head.” Jerry went on to become a spokesman for President Joseph “Erap” Estrada.

Edjop and Jerry were on opposite sides of the political spectrum in the FQS and then each switched to the opposite side with Edjop becoming a hero of the Left and Jerry, who died of a stroke at age 66 in October last year, becoming a spokesman of the Right.

Satur Ocampo, a former House member of the radical left party-list group, Bayan Muna, surmised that Edjop’s switch indicated “either of two things, or both: a) that he found the “moderate” path disappointingly inept or futile; and b) that the drawing power of the “radical” ideas and methods of organizing and mobilization were so compelling, he was swept into the vortex of the national-democratic movement like thousands of other students and community youths across the country, both organized and unorganized.”

THE ROCK OF THE FQS

“Rock” could not be there to join us at the reunion as she was busy with the Women’s Crisis Center she had organized. She would later succumb to cancer on February 28, 2001 at age 53. Her husband, Bobbi, shared a common history with Gary and Jerry. Like them, after being incarcerated by Marcos and later released, he obtained a scholarship to Harvard and also ended up as a presidential spokesman (for Pres. Arroyo).

Mario Taguiwalo was there too, proudly serving as President Cory Aquino’s Undersecretary of Health. “Every time I am tempted to give up on people,” Mario said, “I am reminded of the power of ideals deeply held and I persevere again seeking to convince and not to compel.” Mario would later die of colon cancer on April 22, 2012.

Also present at the reunion were Digoy Fernandez, a former radical from De La Salle who had become a respected banker and Maan Hontiveros, an activist who was now the owner of her own communications company and CEO of her own low-budget airline.

Not present at the reunion were FQS veterans Chito Sto. Romana, Ericson Baculinao and Jimmy Flor-Cruz who were all stuck in China when martial law was declared and who rose to become Beijing bureau chiefs of ABC News, NBC News and CNN.

Singular dream moved a generation

Gary Olivar couldn’t make it to the reunion because he was busy in New York, working as a Sumitomo Bank executive after obtaining an MBA from Harvard University. At my request, he wrote a manifesto for the event, which I read at the reunion, about how “a singular dream moved a generation”.

“A dream so compelling in its inception, so irresistible in its sweep, that it hurled thousands of us against the walls of this palace as if somehow through the sheer weight of our passions on that endless night, we would reclaim the palace for our own.”

“In the conceit of our youth, we believed we could repair the broken bones of a people long despoiled and fulfill a dream of human freedom, of national sovereignty, of equitable progress for every Filipino.”

“Reunions are beautiful,” Nelson mused at the gathering, “because the older we get, the more we cease seeing ourselves as friends or enemies. We are simply survivors sharing a common memory.”

Speaking at the 42nd anniversary of the First Quarter Storm, Satur Ocampo presented a different perspective: “Let us debunk the view of those who regard it as mainly a topic for reminiscences and nostalgia-tripping. Instead let us proclaim the FQS as an epochal event the impact and validity of which pulsates ever more strongly in the bloodstream of the continuing national-democratic revolutionary struggle.”

As we used to chant back in the day, “Makibaka, Huwag Matakot!” (Struggle, be not afraid).

(Send comments to javascript:void(0);Rodel50@gmail.com or mail them to the Law Offices of Rodel Rodis at 2429 Ocean Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94127 or call 415.334.7800.)