NEW YORK CITY–The 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair was ostensibly meant to commemorate the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase from the French, but in reality it showcased the emergence of the United States as a player in the Great Game, as the pursuit of colonial domination was somewhat facetiously referred to then.

As a newly minted world power, the United States wanted a place alongside its erstwhile colonial master Great Britain and other Western powers such as France and Germany. The defeat of Spain in the 1898 Spanish-American War and the subsequent occupation and/or control of its former colonies allowed it to do so, though not without the bloody and brutal 1899 Philippine-American War in the case of the Southeast Asian colony.

The fair was the largest in the world, with more than 1,500 buildings spread over 1,200 acres. The Philippine Exhibit alone took up 47 acres, the fair’s biggest. With 1,100 Filipinos drawn from different regions of the archipelago, from Mindanao Muslims to Igorots in the north, it was by far the most popular draw, and that mainly due to the latter.

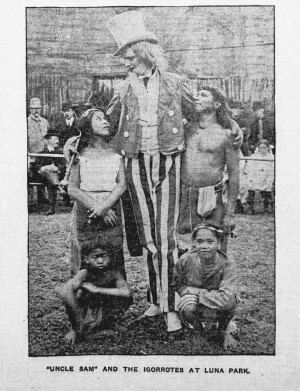

The Igorots made the fair administrators a ton of money. This prompted one of them, an unscrupulous entrepreneur by the name of Truman K. Hunt who had been previously stationed in the Philippines as a medical doctor and subsequently appointed lieutenant governor of Bontoc Province, to return to the islands, recruit his own band of 50 Bontoc Igorots, and exhibit them in various sites in the United States, principally at Luna Park in Coney Island. The trusting Igorots had signed a year’s contract and been promised monthly wages as well as passage back home.

The enterprise was so profitable that Hunt divided the group into smaller groups and had these tour different parts of the country, from Seattle to Memphis. Violating the terms of the contract, he pocketed their wages, prohibited them from leaving the fair grounds and forcibly took from the Igorots the dollars they earned from tips and the sale of souvenirs.

Additionally, taking his cue from the 1904 fair, he required them to consume dog on a daily basis, even though within Igorot culture, this was done only on ritual occasions, surely giving rise to the stereotype of Filipinos as dog eaters. Eventually the federal government got wind of Hunt’s exploitative endeavor and put a stop to it, though Hunt proved a slippery target and got off with relatively light punishment.

This is the little-known sad aftermath of the St. Louis exposition, as detailed in a new book, Claire Prentice’s The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century, a rather stolid but well-documented narrative about greed, racism, and exploitation.

A British journalist, Prentice uses the term “Igorrotes” throughout, employing the antiquated spelling to underscore the fact that this was how the Cordillerans were referred to in the popular media back then. In her telling, there are good guys and bad guys, and a society that seemed on the whole more concerned about the welfare of dogs than of human beings (still very true today).

Of course, one doubts very much that your average white citizen saw the scantily clad, brown-skinned, heavily tattooed men with their head-hunting axes and the women with their bare breasts as fellow humans. To keep the public entertained Hunt concocted publicity stunts that always emphasized the bizarre Otherness of the Igorots. Hunt is an eminently hissable villain who squanders the fortune the Igorots generated at the box office on high living for him and his wife (his third one, by the way) and, increasingly, on drink.

The whole idea behind this freakish display was to provide proof positive that the Filipinos were in need of some benign tutelage. Thus, the primitivism afforded the American viewer seemed to justify President William McKinley’s assertion, encouraged by Rudyard Kipling’s pro-colonial poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” that it was the country’s moral duty to “Christianize and civilize” our forebears, setting aside the rather inconvenient fact that most of the Philippines had been Catholic for three hundred plus years.

While Prentice mentions the Philippine American War (or the “Philippines-American War”), albeit once, she repeats the misleading characterization of nationwide armed resistance to the US takeover as being that of “rebels,” rather than of a revolutionary government engaged in a war to repel foreign invaders, the latter a term she assiduously avoids. No one, after all, would describe the Vietnamese as rebels when they were fighting off the incursions of the US military during the Vietnam War (foretold by the 1899 war against the Philippines).

The most intriguing character to my mind was the young translator Julio Balinag, who served as Hunt’s liaison to the Igorots until it became abundantly clear that all of them (including Balinag himself) were being cheated of their wages, shamelessly and blatantly demeaned and effectively imprisoned within the grounds of whichever fair they had been brought to.

Half-Ilocano and half-Igorot, Julio spoke Ilocano, Bontoc, English and Spanish and dressed nattily in a suit and tie. More than the highlanders he is emblematic of the “little brown brother,” as Filipinos were referred to, moving easily between two worlds and dreaming like most immigrants of a better life for himself and his wife Maria. His type harks as far back as Magellan’s slave or alipin, Enrique, a Hispanicized proto-Filipino who served as Magellan’s interpreter when dealing with the Cebuanos in 1521 and prefigures the overseas Filipino workers who continue to search for opportunities not available in their native land.

Given the colonial context within which this narrative unfolds, there is a mother lode of irony here. After all, the US in its approach to Filipinos and the Philippines was not radically different from Hunt’s own. Subjugating an entire nation supposedly for their betterment was simply ideological cover for the more pressing matter of extracting profit and labor from the colonized. Too bad Prentice doesn’t tease this out. Still, her book does expose this sordid episode in American racial histories. She is wise enough to give one of the Bontocs, Chief Fomoaley, the last word: “I have seen many wonders but we will not bring any of them home to Bontoc. We do not want them there. We have the great sun and moon to light us, what do we want of your little suns? The houses that fly like birds would be no good to us, because we do not want to leave Bontoc. When we go home there, we will stay; for it is the best place in the world.”

Copyright L.H. Francia 2014