Consider how, that since the rise and fall of Marcos, exiled government opponents, aging Filipino showbiz stars and other members of more privileged classes have routinely settled in the US and returned to the Philippines. For some, it’s like jumping on a swinging vine back and forth.

And now, in this Internet era when Bush’s NSA policies continue under Obama, it must be presumed that everyone is under some kind of surveillance.

Even innocent Global Pinoys.

After a local dentist in Daly City was named in a gun-running scandal involving California State Senator Leland Yee and Muslim groups in Mindanao, one must assume more Filipinos than ever are on the radar by both the US and Philippine governments.

Given the global nature of things, it would take a real leap of faith to believe foreign governments of our ancestral countries of origin are not interested in what some of us are doing.

Paranoia? We live in that kind of world. It didn’t used to be that way.

Ah, the good old days, when the FBI would only hound innocent people like artists, writers and activists thought to be Communist Party members.

And that brings us to the subject of today’s American Filipino History Month lesson, the writer Carlos Bulosan.

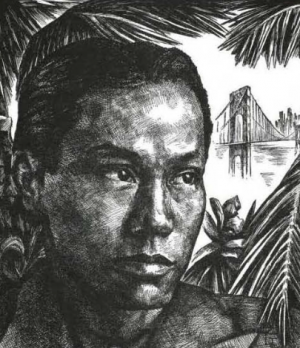

Among Filipino immigrants to America in the 1920s, Carlos Bulosan stands as the community’s literary lion. His semi-autobiographical novel, America is in the Heart, (1946) endures as the seminal story of the American Filipino immigrant labor experience during the Depression.

In that novel, Bulosan wrote: “I came to know that in many ways it was a crime to be Filipino in California. . .I feel like a criminal running away from a crime I did not commit. And this crime is that I am a Filipino in America.”

It wasn’t just his imagination.

Despite mainstream success, including publication in the Saturday Evening Post, from 1946 to 1956, Bulosan was hurt by accusations that he was a member of the Communist Party.

In 2002, I wrote about two Asian American scholars, Lane Hirabayashi and Marilyn Alquizola, who used the Freedom of Information Act to seek the truth about how the FBI targeted Bulosan.

Last year, the scholars wrote about the files they obtained that showed the FBI had its eye on Bulosan between 1946 and 1956.

The FBI ultimately determined Bulosan was not a member of the Communist Party.

But it didn’t change what the surveillance had done to Bulosan’s life. He found himself essentially “blacklisted” and unemployable, unable to make a living as a writer. The surveillance coincided with Bulosan’s heavy drinking and ill health. He died on September 11, 1956.

Recently, Hirabayashi and Alquizola found it wasn’t just the US who was interested in Bulosan’s activities. The Philippine government also wanted to know the writer’s links to the Huks, Communist rebels who fought for land reform in the Philippines.

That fact was first revealed by Professor Augusto Espiritu’s Five Faces of Exile: The Nation and the Filipino American Intellectuals, (Stanford University Press, 2005) from research in the Bulosan archive at the University of Washington.

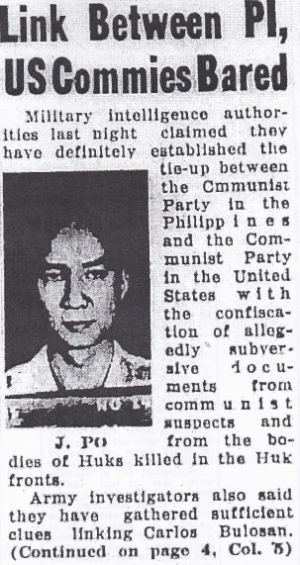

However, Hirabayashi and Alquizola found the actual newspaper article in the Manila Chronicle, dated January, 30, 1951, that shows US military intelligence was somehow involved in working with the Philippine government.

“Link Between PI, US Commies Bared,” blares the front page headline.

All the rest of us who love our freedoms should care because what was done to Bulosan can happen to any of us today–more easily and more efficiently—than ever.