Masoudi, 66, spoke of taking care of the collection of artifacts and works of art in the museum as a huge responsibility to a country ravaged by conflict for 30 years, from the civil war waged by the guerrilla Mujahideen until the Islamic fundamentalist group Taliban came to power.

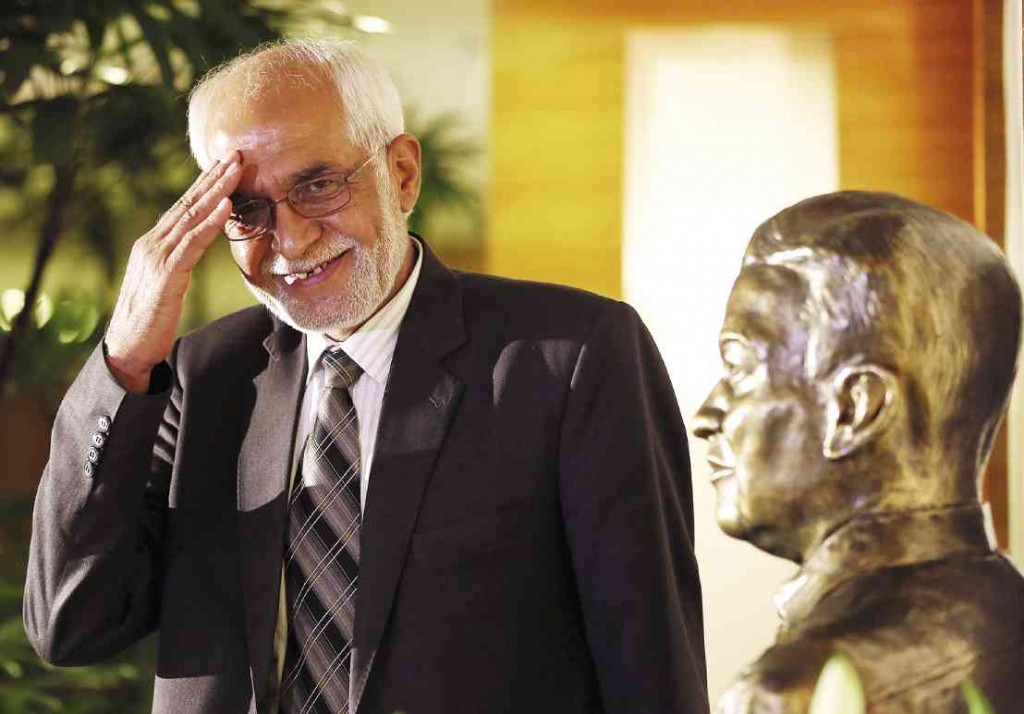

“Once you’ve seen these artifacts you will completely change your mind about us,” Masoudi said in an interview with the Inquirer at the Ramon Magsaysay Center in Manila. “With these beautiful pieces you would never judge the people living in Afghanistan.”

Masoudi flew from his home in Afghanistan to Manila to attend the Ramon Magsaysay Award ceremonies at the Cultural Center of the Philippines on Sunday night.

With five other awardees, the keeper of Afghan culture and history accepted the prize named after the Philippine President who died in a plane crash in 1957.

The Magsaysay Foundation’s board of trustees picked Masoudi for the award in recognition of his “courage, labor and leadership in protecting Afghan culture heritage and rebuilding an institution vital for Afghanistan’s future.”

Like Indiana Jones

“Who would refuse such kind of an award?” Masoudi told a foundation staffer who had phoned him from the Philippines to tell him of the recognition being given him, and if he would accept it.

Masoudi has devoted more than half of his life to preserving the Afghan heritage which has survived through generations.

The brave museum keeper has done his job with love and passion, even against great odds.

His earlier work, which included moving objects like the famous Bactrian treasure of 20,000 ancient gold ornaments to safety, could be likened to that of the fictional character Indiana Jones.

Except that his work is real—and ahead of him is the herculean task of rebuilding a damaged and depleted museum.

For him, Afghanistan’s cultural pieces proving its ancient civilization are priceless treasures war cannot take away from any Afghan.

Lives at stake

A graduate of history and geography at Kabul University, Masoudi joined the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul in 1978. He became its deputy director in 1998.

It was not an easy job as most of the time his own life and safety had been imperiled.

He had seen the museum bombed and looted—acts he described as a “ferocious assault on his country’s patrimony.”

Under a Taliban decree that authorized the destruction of objects considered un-Islamic, the famous sixth-century Buddha statues of ancient Bamyan were bombed and reduced to rubble.

Armed with hammers, members of the Taliban even raided the museum and smashed works of art they regarded as idolatrous.

In secret vaults

Important objects numbering in the hundreds were soon gone. By the 1990s, the cultural and historical heritage of Afghanistan which had been kept in the museum was decimated.

But Masoudi and his team managed to save some of the precious objects, including a cache of some 20,000 ancient gold ornaments belonging to Afghanistan’s ancient Bactria.

They hid the Bactrian gold in secret vaults underneath Kabul’s streets and other safe locations, which were known only to Masoudi and his colleagues.

Selling onions

When the Taliban came to power and conquered the capital Kabul, Masoudi left his job but stayed in Kabul to support his family by selling onions and potatoes on the sidewalk.

But still, he kept an eye on the museum.

“Afghanistan is a Muslim-dominated country and nobody worships statues. But there is a rich culture behind us. We had different religions before and these cannot be erased from our history,” Masoudi said.

Back to museum

“We cannot forget the thousands of years of history that our country has,” he said. “These are our pride and we have to take care of them and save them.”

Masoudi said he kept telling his staff that what had been entrusted to them was a big responsibility.

“We have accepted a very important job of safekeeping the property of our nation and our humanity. We have to do it even if sometimes it seemed impossible,” he said.

When the Taliban rule ended in 2002, Masoudi and his team could finally breathe and move freely.

He returned to the National Museum, where he was appointed its director under a new government led by Hamid Karzai.

Old collections restored

Masoudi then faced a difficult challenge of rebuilding a damaged and depleted museum. But he and his colleagues managed to resurrect the old collections they had hidden and saved.

They led in the restoration of historical monuments and in repairing broken museums.

“It was also a difficult time but with the help of the new government, we were able to do it. We can now see the positive results from our actions,” he said.

Masoudi’s team has also negotiated the return of Afghan cultural treasures which had been smuggled to foreign countries. He also led exhibits abroad to raise funds and promote international appreciation of his country’s heritage.

What keeps nation alive

In 2004, the museum in Kabul was reopened. Despite its depleted collection, roughly 25,000 visitors come to the museum yearly.

In front of the museum in Kabul are words encrypted on a stone: “A nation stays alive only when it can keep its history and culture alive.”

That is the reason Masoudi would risk his life to keep harm away from the objects of Afghan culture and history.

“I see their importance in bringing unity to our country. It will make people want peace,” he said.