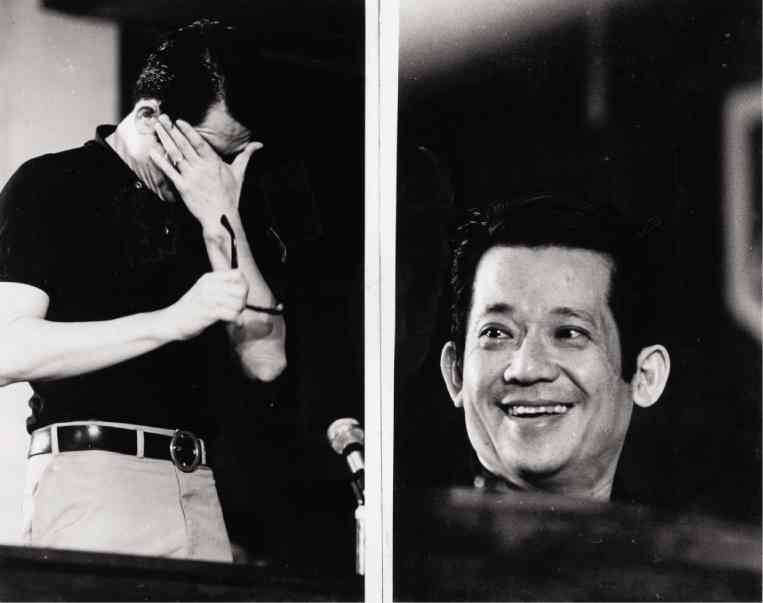

THE TRIAL Aug. 27, 1973, Fort Bonifacio. Sen. Benigno Aquino “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. challenged the jurisdiction and independence of the military commission of Marcos-appointed generals and colonels. He refused to participate in the trial. On Nov. 25, 1977, the military tribunal sentenced him to

die by musketry. ED SANTIAGO

MANILA, Philippines—Sometime early in 1983, I learned from several sources and from Philippine newspaper accounts that Ninoy was dead serious about returning home and that authorities in the Philippines were already planning moves in reaction to this calculated move by Ninoy, taking into account the crucial factor of Marcos’ faltering health. This meant that the latter was not in full control.

Despite my being in New Orleans, I became very much involved with the issue.

Ninoy called me up in New Orleans one early morning, saying, “Brod, help me. I need a passport. I need to travel outside [the United States] and I am requesting your help, please.”

My immediate reaction was, “Senior Brod, I will act on your request. But could you somehow inform Brod Roque (former Ilocos Norte Rep. Roquito Ablan) about this matter.”

For the next week or so, I was consumed by the many questions that the extraordinary request triggered in me.

Should I or shouldn’t I? Why/why not? What can I do and how do I do it?

My dilemma was made worse because I couldn’t talk it out with anyone, as I had to appreciate the situation of the government then. Although martial law was lifted in 1981, it was but in name—the police powers of Big Brother were still in place, not only in the country but more so in the Philippine foreign diplomatic and consular establishments. There was an eye or ear in each post, especially in the United States.

Grave implications

While I was fully sympathetic with Ninoy’s wanting a passport, I felt that whatever response I would make bore grave implications, primarily on my side as a civil servant, a brod, a person.

Selfishly or selflessly, I told myself to act according to my conscience and fidelity to the civil service.

Ninoy called back after three or four days to reiterate his request for help. I felt he was dead serious about his need for a passport. But I still had to hear from Roquito.

When Roquito finally rang me up, he told me, “You can issue the passport to Ninoy. I will have it cleared upstairs.” I asked him, “Manong, upstairs is upstairs. How about [the people] down below, especially the military?”

2 passports, 2 names

Himself aware of the state of affairs then, he responded in Ilocano, “Why, is there a military person or representative assigned over there who would report here?”

I said, “Adda!”—Ilocano for “There is!” He understood my concern so he advised me to be extremely cautious, reiterating that Ninoy’s passport could now be acted upon.

A week later, I met up with Ninoy and handed over to him two passports, one in his name and the other with his nom de guerre “Marcial Bonifacio.” He expressed his gratitude, saying, “Brod, I truly appreciate your kind and brave act. I shall see you in Manila.”

That was in mid-spring of 1983 when we last met. The next time I heard from him was in early August ’83, when he called to confirm that he was set to return to the Philippines and that I should see him when I was back there.

‘Opposition leader shot!’

Past midnight of Aug. 21, I was driving along I-5 on my way home after attending a couple of community functions in the city of jazz. I was then listening to some Cajun music on the radio when suddenly, the music was interrupted with a breaking news item: “Ninoy Aquino, Philippine opposition leader, was shot upon arrival at Manila International Airport. It could not be determined if the shooting was fatal.”

I couldn’t believe what I heard! Driving home as fast as I could, I instantly got on the phone to call Manila. That he was shot was confirmed; hours later, his death was likewise confirmed.

Tears come

I could not hold back my tears, even as I began to speculate on the implications of his death for the country and the people.

For myself, I immediately sensed that there would be some serious investigation of Ninoy’s killing, including how he managed to get a Philippine passport. I could foresee that Ninoy’s senseless [death] would somehow unite the Philippine opposition against President Marcos, upon whom full blame for Ninoy’s reprehensible death would be squarely laid.

Sleepless in New Orleans

For the next month, I had to act as though nothing happened. I was informed that all personnel in diplomatic posts the world over were ordered to check out their consular records to verify where Ninoy’s passport came from. My post in New Orleans was no exception.

However, no trace whatsoever could be located to point to New Orleans as the source.

During the monthlong unearthing of the post’s consular records, I must admit that I had sleepless nights, as I even contemplated the extreme of committing hara-kiri—a foolish thought!

I thought about going on leave but that was even more foolish, as it would only draw unwanted attention. What I eventually did was to try to behave as normally as possible, totally ignoring the matter of Ninoy’s passport.

So I spent most evenings with Filipino community leaders or with some American neighbors to while the time away.

Cherished memory

It is now almost a quarter of a century since Ninoy was shot at the tarmac of the Manila airport that has been renamed in his honor. His aspiration for the country and its people still remain aspirations to be achieved. Monuments, statues, a national holiday—these and many other tributes to him—have been set up to give recognition to this dreamer who asserted that “the Filipino can.”

I take pride in having known a man, my brod, who believed that “the Filipino is worth dying for.”

Ninoy’s promise that he would see me in Manila lingers in my mind. My greatest dream then was to meet him at home… Destiny dictated otherwise.

(Editor’s Note: The writer, now retired from the Department of Foreign Affairs, recounts how he helped former Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. obtain a passport that enabled him to return to Manila, where he was assassinated on Aug. 21, 1983. Aquino had been living in exile in the United States and the writer was then posted as a vice consul in New Orleans. Aquino, President Ferdinand Marcos and the writer were fraternity brothers (brods) of the Upsilon Sigma Phi.

This article was slightly edited from the version that originally appeared in the book, “We Gather Light to Scatter Ninety Years of Upsilon Sigma Phi,” published in 2009.)

RELATED STORIES

24 hours that changed Philippine history

Aug. 21, 1983: One moment in time