But Idzenga had since led a group that not only overcame gravity but also cynicism and racial divides.

The group equipped the mountain settlements with the hydraulic ram pump, an old, nearly forgotten technology capable of bringing a steady water supply to elevated areas using only the raw power of a rushing river or stream.

Everywhere he went at the beginning of his mission, the tall and lanky Caucasian often drew curious stares from the villagers.

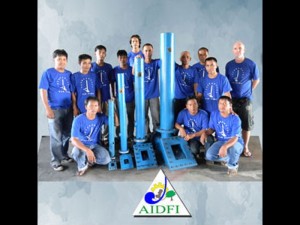

“But when I began talking in Ilonggo, I blended in immediately,” said Idzenga, co-founder of the Philippine-based Alternative Indigenous Development Foundation Inc. (AIDFI), one of this year’s recipients of the Ramon Magsaysay Award.

Considered the Asian equivalent of the Nobel Prize, the award is being given to AIDFI (the lone recipient from the Philippines this year), as well as to five individual honorees from Indonesia, India, and Cambodia. The awarding ceremony is set on August 31 at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

Filipino at heart

He hailed from Holland, but the 49-year-old Idzenga said he had become a Filipino at heart, more so after he married Susan, a Negrense. Like him, their four children speak fluent Ilonggo; “no Dutch or English” spoken in their Bacolod home, he said.

“When I talk, I don’t look at myself and I don’t see my kulay (skin color),” Idzenga said. “I look at myself as an internationalist, but my heart is with the Filipinos.”

AIDFI’s development work has so far centered on promoting the ram pump, but Idzenga and the group’s 20 full-time Filipino members are also developing other self-sustaining technologies, such as one that processes lemon grass into essential oils.

AIDFI was formed in 1991 by a group of activists led by union organizer Leonidas Baterna, who shared his dreams of an “integral and liberating development” with Idzenga.

Their partnership was forged against a backdrop of social turmoil that accompanied the collapse of the sugar industry in Negros in the 1980s. Hundreds of workers and farmers were then displaced, their families sinking deeper into poverty and hunger.

Distrust, suspicion

AIDFI sought to address the basic needs of the affected farmers through agricultural production and technology development. But lack of funds and the loss of key members forced the organization to close shop after only a few years.

Idzenga said this was partly due to the distrust and suspicion among the upland villagers toward non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like AIDFI.

“We had to work really hard for funding because of the bad name NGOs got especially in Negros. In the 1980s when the programs were not implemented well, there were so many NGOs that mushroomed,” he said. “We worked without funding for many years. And there was no government support.”

At that point, returning from a brief visit to his native Holland, Idzenga worked to revive AIDFI, this time giving the group a much clearer focus on rural technology. He came up with his own design of the ram pump and had it patented.

The ram pump uses the natural kinetic energy of flowing water from rivers or springs to push water uphill, without relying on gas or electricity.

The “reinvented” pump introduced by the AIFPI to the Negros uplands can bring water to an elevated reservoir at 1,500 to 72,000 liters per day, according to Idzenga.

Social package

The pump itself accounts for only 10 percent of the cost of the entire “social package” the group brings to the community that would avail itself of the technology.

The package also includes community consultation and technical training, ownership transfer, and the setup of local associations that would manage the water generation and distribution system, as well as financing.

AIDFI also receives donations or grants from businesses, banks and the government, Idzenga said. For example, “we’re talking with Coca-Cola about producing 50 ram pumps a year and they would be paying for them,” he said.

“Landbank is now picking up the technology and offering it to municipalities through loans. We also get some money from the Department of Agriculture for research,” he added.

While most of its projects are in Negros, up to 180 AIDFI initiatives have taken root across the Philippines. The group also managed to set up projects in Cambodia, Afghanistan, Nepal, Malaysia, East Timor, Costa Rica, Peru and even First World countries like Japan and France.

Idzenga said the introduction of the ram pump often became the “triggering point” for development in the communities, like in the case of Sitio Anangue in Murcia, Negros Occidental.

The small village remained poor despite being placed under land reform in the 1980s, he recalled. “The road was very bad. It was very hard for the villagers to cultivate the land. There were no facilities and the community was not organized. They were very much like on survival mode; it was just everybody for himself and there was occasional conflict.”

Organized for first time

“Then we came in with the ram pump,” Idzenga said. “It was the first time the community had any organization of any sort. We completely organized the water association.”

“Then from one village, we got a request from the neighboring village. Then there was a third. So it became three sitios. There’s more cooperation because water came from the same place,” he said.

And soon, the water association in Anangue started exploring other development projects, he said. With the households paying P30 per month for the water, the community found itself with enough funds to go into hog raising and cash crops.

“In the past, this kind of thing never happened in the community. Now they have started cooperating. Now they start thinking of further development,” he said.

City dwellers tend to take water for granted, he said. But in the uplands, “you have to imagine how the people have to go down 80 meters (to fetch water), every day. Try it yourself and carry 40 liters of water on your back.”

“Sometimes kids missed classes because whenever their parents went down to fetch water, the kids would just end up playing and forget about school,” Idzenga said.

Affectionate people

Idzenga said he was drawn to the Philippines as a young man of 22, after hearing many stories about the country when he was still working as a seafarer.

After two decades of living in the Philippines with his family, he said, “I don’t know the difference anymore between living here and in Holland. Everything here is normal for me now.”

Filipinos, Idzenga said, are an affectionate people. “The first thing they do is look at the color (of my skin), but then when we start talking, they warm up and connect. They keep on coming back to talk. It becomes a friendship. Very warm.”

Because of this connection, he said, he had taken great pride in improving the lives of the country’s poorest, especially in places hardly reached by government services.

“The fact that we can bring up water at such volumes for every family, and they don’t have to go down the mountain anymore, that’s a huge, unbelievable transformation,” Idzenga said.

The Ramon Magsaysay Award, Idzenga said, would give his organization a bigger voice for its advocacy. “It fits in our highest objective, which is to spread the (ram pump) technology all over the world. Winning this award will help us reach more villages,” he said.