My friend, the undocumented American

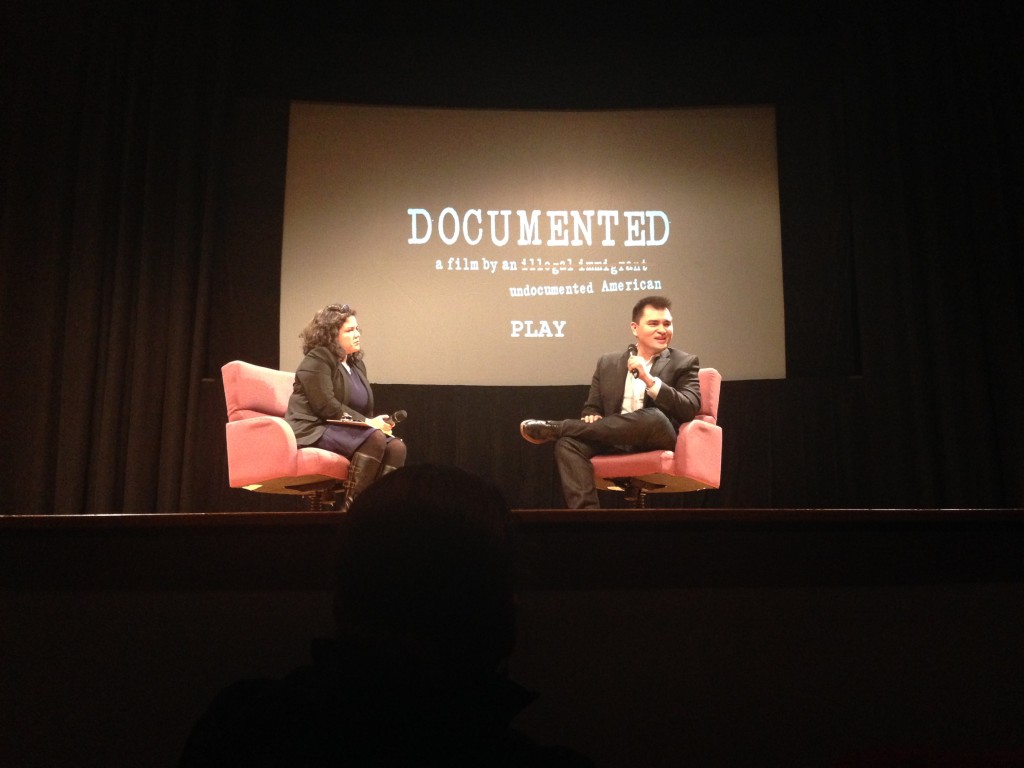

Jose Antonio Vargas at the Oakland, California, screening of his film “Documented.” PHOTO BY PATI NAVALTA POBLETE

SAN FRANCISCO—As a young reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle, Jose Antonio Vargas was a dichotomy in many ways—eager to please, but quick to counter; grateful, yet never satisfied; composed, but perpetually agitated. And even though I was his editor, and later his friend, I never knew his one, most defining dichotomy.

He was an American, yet an undocumented one.

When Vargas eventually left the Chronicle for the Washington Post, I was eager to follow his career. After he won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007 I—standing on the sidelines like a proud ate—had come to expect many great things from him. So when I looked at my phone as it rang at nearly 11 p.m. on June 21, 2011, and saw that it was him, I answered with: “So what are you winning this time?” He responded, “I’m not about to win anything. In fact I may be losing everything.”

The next day he outed himself as an undocumented immigrant, detailing his story in an essay in the New York Times Magazine, and appearing on shows such as “ABC World News” with Diane Sawyer, “The Rachel Maddow Show” and “The O’Reilly Factor.” He used his journalistic skills to explain his story in black-and-white facts— yet he was mired in the gray area of a broken immigration system with 11 million undocumented immigrants, to which he has now become the face.

As I watched my friend on TV, I kept asking myself how he had gotten away with it for so long. Why didn’t he tell me? And most importantly: What’s going to happen to him now?

I recently attended the Oakland screening of “Documented,” the film Vargas wrote and directed, hoping to find the answers to those questions. I expected to see him on the screen navigating the political labyrinth of the DREAM Act. I expected to see him explain how his grandparents living in Mountain View had sent for him, and how he had accidentally discovered he was not an American citizen when he applied for a driver’s license. And I expected to see stories from different parts of the nation as he and his organization, Define American, continued to reshape how immigration is discussed in America.

What I did not expect was the mental and emotional rollercoaster the film took me on. There were clear moments of levity—his lola frying lumpia with a head full of rollers, complaining about her computer-addicted grandson. But the backbone of this film was the heart-wrenching narrative of familial sacrifice, alienation and shame in the quest of a “better life” that was both universal and so painfully intimate. In one of the most touching scenes, Vargas prepares to have a Skype call with his mother, whom he had been regularly sending money to, but had not seen or spoken to in more than 18 years. Vargas explains in the film that it was too hard to face her, talk about her, or even acknowledge to others that she existed. “It’s like we don’t know each other,” he says to her over Skype. “It’s like you’re not the son I used to know. The one who said ‘I love you,’ “ she cries.

Vargas’ mother agreed to send her son to her parents who were already living in the United States, hoping to one day follow him. She knew it was a risk and that he would have no legal documents, but she also knew that he would have more opportunities in America. What she and the rest of his family did not expect, however, was that he would become a successful journalist, with his name on the front of newspapers and his face on national TV. As one of his relatives in the film explained, the expectation and hope was that he would eventually get a “menial” job that would allow him to send just enough money to his mother in Manila, and get married to an American citizen.

Rather than answer the questions I had coming into the movie, “Documented “left me with so many more. Vargas has leveraged every opportunity afforded to him as an American and has contributed his talents and tax money to society. But how many others are out there with equal or greater talent, who stay at “menial” jobs so they can just blend in and earn “just enough money”?

Many immigrant communities had high hopes of the Obama administration coming up with meaningful immigration reform, yet more people have been deported under his administration than at any other time in US history—369,000 in 2013 alone. How do we even begin to tackle such a polarizing issue when even the most likely supporters of reform have failed?

By end-2013, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) reported the population of undocumented Filipinos in the United States as the second-highest at 270,000 among Asian groups. How can we encourage other undocumented immigrants in our community to lift the veil of shame and fear and come forward, contribute to the dialogue, and advocate for reform?

But I suspect these are the types of questions that Vargas was hoping to evoke through this film.

“Documented” is a game-changer of a documentary—one that defies stereotypes, disrupts political discourse and exposes emotion so raw and real that every viewer is forced to rethink what “being an American” really means.

“Documented” will premiere on CNN/US in the second quarter of the year as a CNN films broadcast. To see/learn more about the movie and to see a list of screening dates and locations, go to documented.us. To learn more about Define American, go to www.defineamerican.com.