Devoted doctor in war-torn Yemen

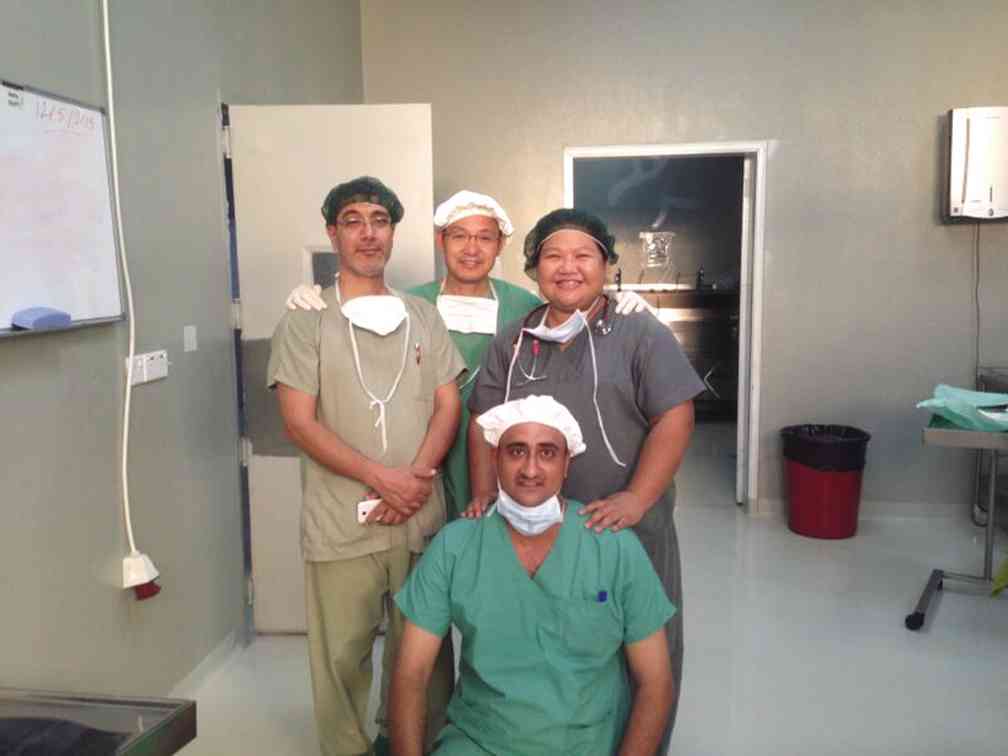

The author (2nd from left) with members of the Doctors Without Borders medical team in Yemen. PHOTO BY MSF

Get down! Get down!” screamed our lead logistician to all the staff onboard the boat. It was the third of July, as I was returning to Aden from Djibouti after a break, when we were welcomed by the sound of gunshots as we were approaching the port of Aden in Yemen.

It wasn’t a good omen. Upon docking, we headed to our hospital, a 35- to 40-minute drive from the port, but we were held at the last rebel checkpoint area for 2 1/2 hours before we were released.

As we left the checkpoint area, a taxi was driving fast trying to catch up with us and we were very distressed by what we saw—a civilian had been shot by a fighter in the back and the bullet went through his abdomen.

On the road, I had to do resuscitation. We rushed him to our hospital for an urgent abdominal surgery.

Welcome to Aden, Yemen. It was my fifth time to be deployed in the country by the international medical organization Doctors Without Borders or Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

My first deployment in the country was in 2013. MSF runs a 50-bed capacity emergency surgical unit in Aden but since the conflict in March the facilities have been overstretched and the number of patients we have at any given time ballooned to a little over a hundred.

The Doctors Without Borders medical team in Aden, Yemen, attending to a patient injured in a bomb blast. BENOIT FINCK/CONTRIBUTOR

Worst year

My recent assignment in Yemen was the worst year I have seen in the country. I saw the country plunge deeper into chaos in four months.

The war between the Houthi rebels and the Southern Resistance forces supported by the Saudi-led coalition has taken a heavy toll on the Yemeni population in all aspects of their lives, including healthcare.

The suffering was taken to the next level. As the main hospital in Aden, being close to the frontline, had closed down, the MSF hospital in Aden was very busy providing lifesaving care.

It was the largest healthcare facility, which receives most of the injured among the four hospitals, still functioning despite the war.

That kept all of the staff, foreign and Yemeni alike, driven in spite of the insecurities and daily risks to our lives.

In the past, the northern part of the country had been plagued by rebellion; the southern part has witnessed the rise of separatist groups.

I have worked in both northern and southern Yemen before the civil war. During that time, the MSF hospital only admitted the relatively few patients who were victims of violence such as bomb blasts, gunshot wounds, etc.

For road traffic accidents, which numbers were once huge for a big city as Aden, cases were referred to public or private hospitals around the city.

Public safety and security concerns were felt back then when the situation was still normal. Healthcare was topnotch with plenty of specialists and health-care workers ready to attend to patients. Hospitals were equipped with complete facilities and medicines.

Height of conflict

But early this year, the security and humanitarian situation quickly took a turn for the worse. In April, the control tower of Aden airport was bombed, making the city inaccessible by air.

Our medical teams in Aden were overstretched and were in dire need of supplies and staff relief as the influx of patients had spiked. The only means to reach Aden by that time was by boat and the journey was 14 to 16 hours long, depending on weather conditions and the waters in the Gulf of Aden could be very temperamental even in the best of times.

I was one of the members of the first team that brought humanitarian and medical aid to Aden by boat amid the height of the conflict.

While we rejoiced when we got the green light to enter Aden, it’s not all fanfare. On the fine afternoon of April 8, as our boat was fast approaching the port on my first trip from Djibouti, I was crushed with what I saw. Aden was no longer the town I once knew. The coastline which was normally teeming with people was deserted.

Cable car lines at an amusement park in the city hung still. The flag at the port’s docking area was at half-staff. It was an eerie feeling as memories of the past years of a busy town and traffic jams were banished by conflict.

Aden was a ghost town. Way back in early 2013, while living conditions in other parts of Yemen significantly deteriorated because of insecurity, the city of Aden was once a vibrant city and relatively stable as foreigners were still allowed to visit some areas that were deemed safe.

We were able to visit the beach, restaurants and other public places, shop for food and visit the fish market. Staff members were allowed to walk from house to hospital (about 300 meters). All that had changed. Especially the hospital, which was now overflowing with patients. The inpatient ward normally had only 50 percent occupancy two years ago, but in July alone it hosted 70 to 100 patients.

Indiscriminate firing

We seldom receive mass casualties but due to the proliferation of arms and armed men on the streets, casual and indiscriminate firing became the norm, so we had patients with gunshot wounds daily.

The MSF team in Aden has tripled its surgical procedures from 300 as of April to over 900 as of July.

To cope with the increasing number of patients admitted due to the conflict, we also doubled our team members—from the normal two to three staff members (surgeon, anesthetist and operating theater nurse) plus an orthopaedic surgeon and a general surgeon.

The influx of patients forced us to double the capacity of the hospital with some patients recuperating on mattresses in our meeting room and one physiotherapy room was hastily converted into an in-patient ward.

Currently, our team in Aden needs an intensive care doctor because we have many critically ill patients requiring specialized care and medical attention.

Our other ward doctors can no longer cope with the needs. Most of the time, while on duty, I had to set aside my own problems. Yemenis need our help more. They live day by day without food, fuel, electricity and water.

The medical needs of the civilians and the fact that our hospital is the only facility fully functioning in Aden during the war keeps my team going.

Heavy shelling

I remember the times when there was heavy shelling everywhere, the explosions were getting closer and closer to the hospital, and all I prayed for was the safety of my team and to make the shelling stop.

Being close to the frontline, we heard the shelling and bombing up close and we felt the ground shaking. The hospital building shook; sometimes there were stray bullets either hitting the walls or shattering the windows. When encounters like these happen, we would receive a fresh influx of patients.

It was during those times of physical, psychological and physical stress that one of our patients in intensive care lit up the world I was in. He had a bad gunshot wound in his back and suffered serious complications which meant he could no longer eat solid food. He became so thin and frail. In fact I needed all the help, medication and equipment I could find for his condition. He had the worst complications among the patients in the ward but he was the most optimistic of the lot.

He was so compliant. He didn’t normally drink milk but he gulped it all down because he said I told him to do so. He was the first one to greet me whenever I enter the ward and ask how I was. Amid the tension and depression, someone like him still has a smile on his face.

“You have a good heart doctor, I pray that you will have many more years of blessings from God …” he said.

I had to leave the ward because I didn’t want him and the other patients see me crying. People often ask me why I do what I do? It’s for patients like him.

(Aquilar is an anesthetist from Muntinlupa City, Metro Manila, who joined Doctors Without Borders or Médecins Sans Frontières in 2012. She has been to Pakistan, Haiti, and the Central African Republic and just recently returned from conflict-torn Yemen. Currently, she’s in Manila waiting for her next assignment.) CDG

RELATED STORY

750 migrants rescued from boats off Libyan coast—MSF