Picking up the pieces: Leaves from the same tree?

NEW YORK CITY — Sometime in the latter half of the 19th century a man by the name of Marcos Francia left the Tagalog region in Luzon and moved to the Visayas. Why he did so isn’t clear. Perhaps he was fleeing an unhappy marriage. I raise this possibility because in Cebu, where he resettled, he took on a mistress, Clotllde Rubi, daughter of a prominent Cebu family with roots in Mactan. They never married even though they had a son in 1888, Raymundo Francia. A scandalous situation, given the ultraconservative Catholicism then in place—hence, my suspicion that Marcos couldn’t tie the knot with Clotilde.

Marcos, Clotilde and Raymundo lived in Cebu’s Parian district which, writes Romola O. Savellon, an art historian and professor of literature at Cebu Normal University, “was then the enclave of Filipino-Chinese and Spanish-Filipino mestizo families and the outpost of the local principalia. Raymundo must have blended well with the residents there considering his mestizo features. As a young boy, he taught himself how to draw, paint and sculpt.”

Savellon titles her essay, “Raymundo Francia: Cebu’s Michelangelo,” not necessarily to imply that Raymundo’s artistry was as powerful as that giant of Renaissance art’s. She makes the comparison since Raymundo, as Michelangelo did, lay on his back while painting church ceilings. She adds this tidbit, provided by Raymundo’s son, Edilberto: “When his hands grew tired, Raymundo would hold the brush with his toes and go on painting with the same dexterity.”

Savellon’s piece is included in Kisame: Visions of Heaven on Earth, a catalogue that accompanied a 2008 photographic exhibition of Bohol church murals at the Ayala Museum in Makati, and guest- curated by Manila-based Fr. Milan Ted Torralba, responsible for arranging my tour of the churches. Fr. Agerio Paña, Tagbilaran’s diocesan chancellor, was kind enough to give me his copy over breakfast at the rectory, hours before my return flight to Manila once he found out my family name.

Raymundo grew to be the most prominent painter of churches of his generation, not so much in Cebu but in Bohol, along with Canuto Avila. (Bohol for a while was part of the diocese of Cebu.) The two, sometimes working in tandem, more often separately, were particularly noted for the murals they painted on the ceilings of approximately 20 Spanish- and American-colonial churches that dot the landscape of Bohol—an island that, as I noted in my previous column, may have the highest number of colonial-era churches, many of them severely damaged, if not demolished, by the earthquake of October 2013.

Raymundo also painted portraits, only one of which survives (the others were lost in a fire): that of Pope Pius III, now in the Vatican collection. The painter passed away in 1975 at the ripe old age of 87. Leading a bohemian life, he earned handsome fees for his work but was generous with his money. He may have painted religious scenes for churches, but he was no saint. Per Savellon, “He sired several children by many women, none of whom he married.”

I first heard of this painter with whom I share the same family name a few years back, when I was sightseeing with a group of writers and students. The church at Baclayon was one of the places we visited. We walked around the cool interior admiring the retablo and the hoary santos. Before we left someone mentioned that apparently one of the mural painters had the same surname as I did. Of course, the name resonated and made me wonder if we were kin, if in fact this artist was of a branch of the tree that had been planted in the Tagalog region, specifically in Laguna, in the Santa Cruz-Pagsanjan area, where the Francias are from. At any rate, I filed this in the recesses of my brain, to be examined once more when the right occasion presented it.

That occasion was on my last trip, noted in my previous column. Unfortunately, two of the churches on my itinerary that had Raymundo’s works were in no condition to be examined closely or even seen. In the case of Loon, the church was reduced to rubble. In other instances, his works, as was also the case with Avila’s, had been either whitewashed or painted over—an indication that parish priests while well meaning are not necessarily the best conservationists of what they are guardians of. This issue of who has the ultimate responsibility for protecting these works, whether it is the parish itself or a public institution such as the National Museum and/or the National Commission on Culture and the Arts, is a delicate and thorny one, but it needs to be resolved in a way that protects this historical patrimony.

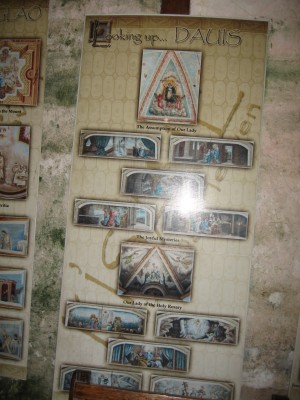

It was in the town of Dauis where I noticed a plaque that attested to the church complex being designated a national heritage site and, more significantly for my purposes, mentioning both Francia and Avila as having painted works (“pintadong obra”) between 1919 and 1923. There was also a compilation of photographs of the art. I have included shots of both the plaque and the compilation here.

My curiosity has been piqued by this discovery, for the obvious reason that such a well-regarded artist may have been a kinsman. I hope to learn more about this man, and meet some of his descendants the next time I am in the Visayas, there to wander once more those hallowed precints in search of buried time.

Copyright L.H. Francia 2015

Like us on Facebook