The Filipino who made a prized, world-famous basket

A selection of authentic and “in-the-style-of-Jose Reyes” baskets at a Nantucket Antiques store. The look is not patented, but Reyes and other basket makers sign or apply labels on their creations. YOUTUBE SCREENGRAB/SYLVIA ANTIQUES

First posted in PositivelyFilipino.com (as ‘Love Baskets for Betty’)

Remember the old Patti Page standard, Old Cape Cod, which sang of “sand dunes and salty air, quaint little villages here and there”? If you do, then you’ll get the right coastal New England setting of this story. Or if you are an “Antiques Roadshow” aficionado and happened to catch this episode https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/archive/201002A26.html, then you would have seen the moment when appraiser Leigh Keno identified the “Jose P. Reyes Friendship Baskets” halfway through it. Two questions then immediately spring to mind:

- Where is Nantucket?

- Who was this Jose F. Reyes of Nantucket-basket fame?

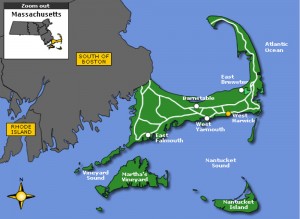

Answer to question 1: Nantucket is an island off Massachusetts in the Atlantic; southeast of Boston and due south of the extended arm of the Cape Cod peninsula. It is east of Martha’s Vineyard (setting of “Jaws.” See map.) Nantucket used to be an old whaling community. While it never became as prosperous as New Bedford up the coast or Hartford to the south, it became famous for its treacherous shoals (the Nantucket Sound).

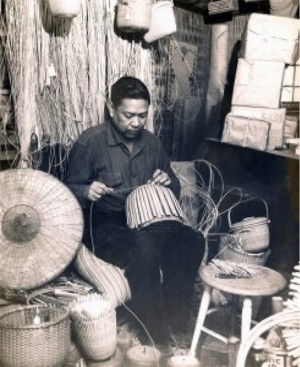

Jose F. Reyes at work in his basket studio in Nantucket, circa 1970. Note the salakot on the left side. The studio was donated to the Nantucket Historical Association. NANTUCKET HISTORICAL ASSN PHOTO

Being the island farthest east, Nantucket also became third choice, after Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, as the summer watering hole of prominent Bostonians and New Englanders. But there is also a year-round community of locals on Nantucket who are not quite as socially placed as the summer habitués – and that is where our cast of characters eventually settled.

For question 2, that is one Jose F. Reyes from the faraway Philippines, who despite earning a master’s degree on scholarship (!) from Harvard University in the early 1930s, found his true calling — making woven baskets half a world away in quaint, old Nantucket. The name “Jose F. Reyes” rattles many a pocketbook in basket-collecting circles with his unique baskets, which fetch a few thousand dollars in today’s market.

Basket weaving was not an entirely new craft to Nantucket. As early as the 1700s, the Wampanog Indians, the original inhabitants of the island, were known to weave their own baskets. When the island became part of the colony and Commonwealth of Massachusetts, white settlers, whalers and sailors took up the craft of basket weaving to while away the long days on whaling sorties – and especially when they were on duty on the lightships (more on that later). However, those baskets were free-form and bore little resemblance to the baskets Nantucket is known for today.

Genuine Ilocano

Our story actually begins in the small provincial town of Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur, where Jose Reyes was born to parents of modest means, Eugenio and Maria Reyes, in September 1902. The oldest of ten children, Jose then bore the burden of setting a good example to his younger siblings by getting the best education that their meager circumstances would allow. A young Jose got exposed to the rudimentary basics of basket-making in arts & crafts classes at the local elementary school, but little did the lad know that this cottage-industry knowhow would lead him to an altogether different direction later in life.

At around 14, Jose already was on his own. Somehow, he ended up going to Washington High School in Portland, Oregon. This was followed by a scholarship to the local Reed College, established 1911, where Jose earned his bachelor’s degree in education, becoming the first Asian graduate of the school. This was in the mid-1920s, into the third decade of American rule in the Philippines, so visa matters weren’t a problem at all. It was at Reed where Jose met one Mary Elizabeth (“Betty”) Ham. Jose and Elizabeth knew there was something special about their relationship even though it was too early to make any permanent commitments.

Jose’s first undergraduate scholarship at Reed was followed by a post-grad one at Harvard University, that most vaunted of U.S. educational institutions. It seemed serendipitous that Jose ended up in Harvard – then very much the purview of America’s elite white classes – for Betty was originally from Cambridge. They met up in the Boston area again and continued their relationship.

But while Jose pursued his master’s in education at Harvard at the height of the Great Depression of 1929 no less, Betty was forced to go to St. Louis to finish her nursing degree at Deaconess College of Nursing. On completing their respective degrees, Jose and Betty married on Valentine’s Day 1933, against great objections from Betty’s family.

Disapproval and the Depression

Further ignoring the senior Mrs. Ham’s disapproval, and with the Depression ending, the newlyweds made plans to start a new life and a family in the young Commonwealth of the Philippines. Reestablished in Manila, Jose first taught art and English at the University of the Philippines in Padre Faura. But having always wanted to teach social studies, Jose got a better offer from the Philippine Military Academy (PMA) and moved to Baguio. At the PMA, he was made head of the Department of Languages and Social Arts. The following years were uneventful save for the expansion of the family with three children.

In early 1941, with the threat of war with Japan imminent, Jose joined the U.S. Army and was appointed Secretary to the General Staff. In December 1941, the inevitable happened – Japan attacked both Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. With the dismal turn of events, the PMA was disbanded and the Reyeses were forced to move; first to Mandaluyong and then later in the war, to Malolos, Bulacan.

The young family was severely tested during the Japanese Occupation especially because Jose was an enlisted U.S. Army man and Betty was an obvious American lady. But they kept a low profile, and Betty was passed off as a Spanish mestiza since the Japanese occupiers did not really bother Manila’s Spanish community very much. Most of the known civilian American and allied community were already incarcerated at the University of Santo Tomas. In the meantime, the kids were growing up fast.

When the islands were liberated in May 1945, the Reyeses faced another pivotal turning point in their lives. Having survived the war for the most part unscathed, Jose and Betty elected to return to the U.S. even before Japan’s formal surrender in August that year. The family was on the first civilian ship out, which was ferrying sick and wounded American soldiers back to the States. Betty, of course, was able to apply some of her nursing skills on the wounded soldiers on the trip.

Not exactly heaven

The big question seemed to be why? With the promise of a new country and both husband and wife having the credentials to help build a new republic, why did Jose and Elizabeth choose to leave great self-fulfilling potential behind and face uncertainty and possible discrimination back in New England? Did Elizabeth miss her New England roots that much to put her family through that? That was part of the answer. The young couple did not have enough faith in the promising new country and preferred to raise their children in the “safe” setting of the U.S. They would cast their lot with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts rather than the old one of the Philippines.

Meanwhile, Reyes was formally discharged from the U.S. Army with the rank of captain and automatically received U.S. citizenship in 1947. That summer, the couple’s relations with Betty’s mother started to thaw such that they were invited to rest and recuperate at her Nantucket property. Like many who had vacationed on the island, Reyes and his family fell in love with the place and knew they had found their new home. They never left Nantucket, although Jose had to return to the new Philippine Republic sometime in 1947 for some family business.

When he returned to the States, things still weren’t easy for the mixed-race couple in their new home. Reyes had a master’s degree from Harvard and real-life experiences from halfway around the world, so one would think that he could easily find a teaching position. No such luck. Even in so-called “liberal” New England, discrimination reared its ugly head in oh-so subtle ways. Jose was unable to find even a halfway decent teaching job, so he had to settle on working blue-collar ones, painting houses and repairing cane-and-rush chairs during the warm-weather months, while Betty took odd nursing jobs to feed their growing family.

In the winter months, Jose started basket weaving with one or two of the remaining practitioners of the craft on the island. His early basket weaving training as a boy in the Philippines came in handy and helped him and his growing family survive. With that, Reyes finally found his calling.

When the business started to take off, Reyes needed a marketing hook to differentiate his land-made-baskets-with-a-lid from the island’s other baskets. In 1948, a picture in Life magazine showed a basket with a cloth top. Jose appropriated that idea as his own; and he called his hybrid creation, the Jose Reyes “Friendship” baskets.

A reputation and legend started to build around his handicraft. A well-known vignette tells of one American woman in Paris sporting her Reyes basket while walking down a fashionable street. Across the way, she sees another woman with a similar basket. So she hollers across the street, “Nantucket!” and raises her basket, hoping to catch the other woman’s eye. Indeed she does, and the other woman acknowledges her as well. The two women, strangers to each other at the time, become friends over a cup of coffee – brought together by the shared pride of owning a Jose Reyes Nantucket basket.

The Massachusetts mainland, Cape Cod (the arm curling up), Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Island (lower right). MASSACHUSETTS TOURISM INFORMATION

Anyway, the legend was not discouraged, and thus the “FriendSHIP” basket was born. It was as good a marketing hook as any–maintaining a “maritime” connection with the sea but still not misrepresenting true origins vs. the other baskets made on the island.

The “Jose P. Reyes Friendship” basket was not a patented name or look, and eventually other Nantucket basket makers adopted the style and, in so doing, paid homage to Reyes who some credit with almost single-handedly reviving a dying craft with the simple innovation of adding a lid. (The scrimshaw carvings on the basket lids were a later personalized addition by other artists.) Many Nantucket historians today demarcate the history of basket making on the island as “pre-“ and “post-Jose Reyes” periods.

Legend

So popular had Reyes’ Friendship baskets become, that he built up a backlog of several months to two years for new orders. He became so busy at times that he had to post a sign on his counter saying: “No Repairs Until Next Year.” Thus in 1952, when the colony of expatriate British ladies living in Nantucket wanted a special gift for a very special occasion in London in June 1953, they had to put in their order the fall before. The special order was just for one signature basket, a Jose Reyes Friendship basket, as the island’s gift to the young Elizabeth Windsor-Mountbatten, who was being crowned queen of the United Kingdom in June 1953. How many other basket weavers could make that royal claim? Not too many.

Today, Reyes-made-and-signed baskets sell anywhere from a regular $2,500 to one basket that changed hands at a private sale for just under $20,000. One basket similar to the one pictured at the top of this article, sold for $4,950 on eBay on March 14, 2014. By the time Reyes retired in 1978, it was estimated that about 5,000 baskets had passed through his own hands (and he signed most of them), and he still had a four-year waiting list to fulfill. His son and granddaughter helped fulfill some of the backlog.

In his retirement years, Reyes threw himself into the social life of the year-round Nantucket community – the local Rotary Club chapter, the Masons, the Men’s Club, the PTA, the Boy Scouts and the Congregational Church Choir.

On Christmas Eve 1980, Reyes died at home in his beloved Nantucket. Thus ended the bittersweet tale of Jose Formoso Reyes, originally from the Philippines but whose latter-day fame was tied to another island half a world away. He was a self-made youth who came from tropical, faraway, rural Ilocandia, who faced the trials and tribulations of true love and discrimination in his adopted homeland. Yet he made his mark in the cold, alien, blustery world of a remote North Atlantic island. And that’s the story of perhaps the most highly educated master basket maker the world has ever known.

Lightship vs. Friendship

Strictly speaking, the earlier generation of baskets made in Nantucket were “lightship” baskets, i.e., made onboard the lightships, which sat on the treacherous Nantucket shoals. “Lightships” were essentially floating lighthouses but provided more than just service at night. They were anchored over the most dangerous stretches of the regular shipping and whaling ship lanes. They not only provided light guidance at night, but also cautioned mariners unfamiliar with the Sound to stay away from particular areas as the underwater terrain is shallow and hazardous to the vessels.

Crews normally served on 30-days stretches on the lightships. Thus, to while away the time on board, since they didn’t embroider, crochet, play crossword or video games, they resorted to handicrafts such as carving scrimshaw or weaving baskets–the next best thing to macrame. Where did the wicker (known as rattan in the Philippines), not indigenous to the area, come from? Whaling ships brought back most of the wicker from their sorties in the Caribbean and other exotic ports.

Myles Garcia is a retired, San Francisco Bay Area-based author and writer. His proudest work to date is “Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies.” In between writing (currently finishing a play), he is learning how to play the piano — late in life, to complement his cabaret singing skills. Better late than never.

For more stories on the Filipino diaspora, go to PositivelyFilipino.com

Like us on Facebook