Filipinos in San Francisco a century ago

Years ago, Abe Ignacio was surfing on eBay when he was stunned by one item for sale.

Years ago, Abe Ignacio was surfing on eBay when he was stunned by one item for sale.

It was a cover of an 1899 issue of Judge magazine showing President William

McKinley scrubbing what was supposed to be a Filipino child, saying, “Oh, you dirty boy.” The caption read: “The Filipino’s first bath.”

That discovery led Ignacio, in cooperation with three other Filipinos — including Jorge Emmanuel, Helen Toribio, Abe’s late wife, and Enrique de la Cruz — to write “The Forbidden Book,” a compilation of racist portrayals of Filipinos during the Philippine-American War.

I wrote about a 2001 exhibit in Berkeley based on the collection for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Abe has continued digging since then, finding a rich gold mine of information and photos at the San Francisco Main Library, where he is now a guest scholar.

One of the items he found recently offers a different portrait of San Francisco, which is now considered one of the most liberal and open-minded cities in the world, where Filipinos have one of most vibrant and established immigrant communities.

Just last month, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee announced that Tagalog is now the third required language, in addition to Chinese and Spanish, covered by the city’s language access ordinance.

It showed the respect the Filipino community commands in San Francisco.

Well, that wasn’t always the case.

This was evident in a shameful, though forgotten, chapter in the city’s history. It happened 109 years ago, in 1905, when a group of 25 tribal Filipinos from the Cordilleras endured the humiliation of being put on display in San Francisco.

In the San Francisco media, including my alma mater San Francisco Chronicle, they were called Igorots, long known as a derogatory term for people from the mountainous regions of northern Philippines. The group was part of the more famous exhibition called Philippine Village at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair, organized by a soldier-turned-business named Richard Schneidewind.

The show was a hit. In a blog post, Abe and Mitchell Yangson, librarian of the San Francisco Main Library’s Filipino center, quote anthropologist Patricia Afable who wrote that, in the age before mass media, “the display of exotic objects and peoples in midways and sideshows was a major source of entertainment throughout the Western world…For some years, ‘Igorot’ filled a niche in this entertainment industry, along with Native American peoples and Africans; and these displays were never too far from the stalls of ‘dwarfs,’ ‘bearded ladies,’ and the like.”

While the St. Louis exhibit is fairly well-known, I actually didn’t realize that the tribal Filipinos also made an appearance in San Francisco. The so-called “Igorotte Village” was set up in the city’s Central Park near where the San Francisco Main Library now stands.

It was, of course, an incredibly racist era.

According to Ignacio and Yangson’s research, researchers from the UC Berkeley anthropology department took measurements of the visiting Filipinos, and published their findings in the journal, American Anthropologist.

“Looking back on this act of physical measuring, one must place it within the context of the philosophy of Social Darwinism that established a hierarchy of superior and inferior peoples,” they write. “At the top of the rankings would be the Anglo-Saxon Americans, English, Germans and French and then their darker inferiors. The Philippine highland peoples or Igorrotes were placed in the lower rungs of civilization.”

The San Francisco media had a field day, naturally.

An ad in the San Francisco Chronicle announced the exhibit of “head-hunting, dog-hunting wild people from [the] Philippine islands.”

A story in another newspaper, the San Francisco Call, carried the headline “Dogs Fleeing from Stewpot: Igorrotes Devastate Canine Population and Nobody’s Towser is Shown Mercy.”

“One of the negative legacies that endure still today is the idea of all Filipinos being dog eaters,” Ignacio and Yangson write. “The 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and the subsequent nationwide and European tours through 1913 did much to nurture this racist stereotype.”

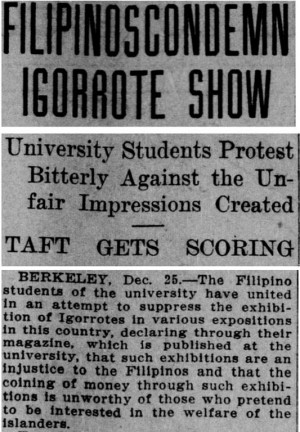

But Ignacio and Yangson also uncovered a historic tidbit that I found very interesting: some Filipino Bay Area residents actually protested exhibit. Most of them were Filipino students at UC Berkeley who eventually helped pressure the U.S. colonial government in the Philippines to put an end to the use of Philippine tribal people for such exhibits.

Ignacio and Yangson write that the students worried that “these displays would create the impression that all Filipinos were primitive naked savages,” which suggested that the protests were not based on a form of outrage over the way their fellow Filipinos, who happened to be from tribal groups in their homeland, were being treated.

Fortunately, times have changed.

“Today, many Philippine highlanders, now embrace the “identity of ‘Igorot’ and call it a ‘name of pride’ rather than a ‘name of shame,’” Ignacio and Yangson write.

Ten years ago, in 2004, they even held a “grand reunion” to mark the centennial of 1904 St. Louis Fair.

Some of the tribal Filipinos actually never made it back to their homeland during their infamous tour of America. At the reunion, memorial service was held “for their ancestors, especially for those who died while in America a century ago,” Ignacio and Yangson write.

Visit and like the Kuwento page on Facebook at www.facebook.com/boyingpimentel

On Twitter @boyingpimentel